The Hibiya Riot is famous for being the first major social upheaval in modern Japanese history. Angry at what was perceived to be the disappointingly minor concessions gained following the end of the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, a heterogenous group of lower and middle class rioters brought Tokyo to a standstill for three days, at the end of which 311 people had been arrested, and 17 people were killed.

Japanese propaganda had obscured a Pyrrhic ending to the conflict. Japan had suffered 80,000 fatalities in a drawn-out, attritional war, with total costs incurred coming to 1.7 billion yen; eight times the cost of the Sino Japanese War of 1894-1895. Andrew Gordon’s account hence demonstrates clearly how public fury was directed at visible signs of Government authority. For example, nearly three quarters of all the neighbourhood police boxes were destroyed in the city, whilst clashes resulted in injuries to 450 policemen and 50 firemen.

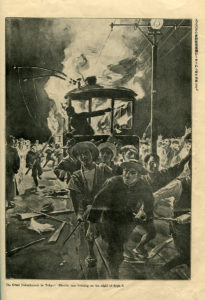

However, the roots of this riot can be found in more than just anger over tainted national pride. There is also evidence for a more subtle, economic dimension to this groundswell of popular protest. Besides the police boxes, the other public institution to be specifically targeted was the recently opened streetcar system. Tokyo had invested heavily in its tram system as a potent symbol of the new Imperial and democratic Japan. However, they were expensive, and beyond the means of many of the city’s lower classes. They were also a disruptive presence, threatening the livelihoods of thousands of rickshaw drivers in the city. Nor indeed was this a one-off occurrence. Upon the anniversary of the riots, a rise in streetcar fares spurred a new rally in Hibiya Park, which again ended with the smashing of dozens of streetcars, as well as an attempt to storm the streetcar offices. [1]

Image from The Tokyo Riot Graphic, No. 66, Sept. 18, 1905, (Kinji Gahō Company, Tokyo)

Such a case therefore illustrates the simmering tensions between the ‘old’ city of Edo and the ‘new’ metropolis of Tokyo. The transition between the two is discussed by Henry Smith in the ‘Edo-Tokyo Transition’. He refers to the distinction in Japanese intellectual thought between the shitamachi and the yamanote. Whilst they began as geographical designations (shitamachi referred to the lower class Eastern downtown of the city, whilst yamanote was associated with the elite Western upland areas), Smith argues that by the early 20th century, they had come to embody two competing ideological frameworks, with the former representing the old, traditional ‘plebeian’ ethos of Edo, whilst the latter instead heralded the new, modern and Imperial Tokyo.[2]

What conclusions can be drawn from this? In terms of the destruction of modern technology, there are obvious parallels between the Hibiya Riot and the 19th century Luddite movement in Britain, where textile workers attempted to destroy textile machinery that threatened their employment.[3] What is interesting about the Japanese case though, is how this struggle against streetcars formed part of a deeper, ideological battle for the very soul of the city; with competing notions of modernity versus tradition helping to shape urban social protest in early 20th century Japan.

[1] Andrew Gordon, ‘Social Protest in Imperial Japan: The Hibiya Riot of 1905’, MIT Visualising Cultures, < https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/social_protest_japan/trg_essay01.html> (accessed 9/12/2019)

[2] Henry Smith, ‘The Edo-Tokyo Transition: In search of Common Ground’, in Marius Jansen and Gilbert Rozman (eds.), Japan in Transition: From Tokugawa to Meiji, (Princeton, 1986), pp. 370-374

[3] Evan Andrews, ‘Who Were the Luddites’, in History Today, (26.6.2019), <https://www.history.com/news/who-were-the-luddites> (accessed 9/12/2019)