Although separated by over three thousand kilometers, Korea and the area formerly known as French Indochina (Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and Guangzhouwan China) share similar weather, and every year for roughly a month they endure a monsoon season. Today, the potential dangers of these monsoons are adequately eliminated as a result of modern infrastructure, which did not appear out of the blue. In the early twentieth century in Japanese colonized Korea and French Indochina, officials began concerning themselves with city planning regarding flooding caused by monsoons. Although preventing flood damage was not the only goal in mind, this piece will focus specifically on the different approaches taken by the Japanese and French Government-General in order to solve issues of flooding.

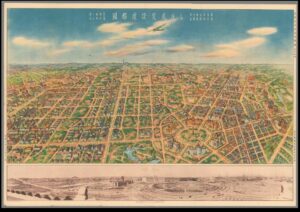

In Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945, Todd Henry analyzes the Japanese Government-General’s attempts to transform Keijo, modern day Seoul, into “Great Keijo.”1The Japanese Government-General had an underlying goal in the creation of a “Great Keijo.” Henry explains that Japanese officials sought to create a ‘showcase city’ of Japanese modernity.2 In other words, city planning in Keijo was a demonstration of Japan’s civilized status to the West; city planning prioritized image over function. With this in mind, flooding issues in Keijo was of little concern to the Japanese Government General. Henry reveals that by 1912 citizens of Keijo expressed concerns regarding monsoon flooding of the Hanh River.3 Japanese officials responded with a multitude of short term solutions which inevitably failed. According to Henry, city planners mostly ignored these flooding issues until a flood in 1925 which caused roughly four hundred deaths and forty-six million yen in property damage.4 This event finally brought the issues of flooding to Japanese officials’ attention; unfortunately, Henry indicates that “the Government-General continued to pursue its own plans to transform Keijo into a showcase city.”5 From Henry’s analysis of the Government-General’s efforts in flood prevention, it can be seen that in the city planning of the ‘Great Keijo’ Japanese officials were concerned with validating their position as a ‘civilized’ nation rather than the function of their plans.

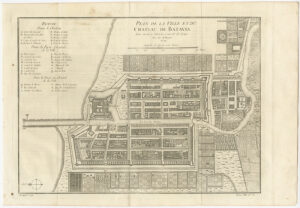

On the other hand, France was already considered ‘civilized’. As a result, the French Government-General in Indonesia’s city planning efforts were concerned with function over image. In 1912, Jules Sion writes about the major importance of rainfall in the lives of the native population, and consequently rainfall in the French Indochinese territories must be scientifically studied.6 Sion’s article addresses the negative aspects of the shutting down of rain measuring stations in French Indochina. He argues that, given the importance of rainfall for the Indochinese population, rain measuring stations must be re-opened for scientific research; more importantly, he emphasizes that rainfall must be measured in order to prevent destructive flooding.5 Additionally, Sion acknowledges the urgent necessity of building roads and railways, but the absence of rainfall measurements will lead to inevitable missteps.7 Evidently, Sion is advocating for the reopening of rainfall measurement facilities in order to benefit nation building and infrastructure construction. Moreover, in 1930, Charles Robequain also discusses the importance of rainfall measuring stations in French Indochina; however, this time, it is to discuss the positive efforts of the Government-General. In accordance with Sion, he insists on the insufficient number of rainfall measuring stations in Indochina in 1912, and that the development of rainfall measuring stations would limit the destruction of floods.8 He fortunately reveals that at the end of 1928 the number of functioning rain stations were 338, as opposed to only 150 in 1926.5 This swift re-opening of these stations by the French Government-General highlights the prioritization of flood prevention by French officials.

By comparing the efforts of French and Japanese officials in flood prevention, it is evident that they had disparate goals. While Japanese officials ignored the needs of flood preventing infrastructure in order to assert themselves in the ‘civilized’ world, the French saw the rain’s destructive ability and established stations which gathered scientific data in order to predict future meteorological destruction. Admittedly, rain played a different role in both spaces. In Indochina, understanding rainfall was not only important to prevent destruction, but it was also paramount in growing its mostly agricultural economy. Nonetheless, while the Japanese Government-General focused its city planning on the impression it would make on the world, the French Government-General implemented stations in order to aid the Indochinese population.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources:

Robequain, Charles, ‘Le climat de l’Indochine française’ Annales de Géographie, 39:222, 1930, pp. 651-653

Sion, Jules, ‘Les Pluis de L’indochine’, Annales de Géographie, 21:120, 1912 pp. 462-464

Secondary Sources:

Todd A. Henry, Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945, (California Scholarship Online, 2014)

- Todd A. Henry, Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945, (California Scholarship Online, 2014), p. 42 [↩]

- Todd A. Henry, Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945, (California Scholarship Online, 2014), p. 31 [↩]

- Todd A. Henry, Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910–1945, (California Scholarship Online, 2014), p. 47 [↩]

- Ibid [↩]

- Ibid [↩] [↩] [↩]

- Sion, Jules, ‘Les Pluis de L’indochine’, Annales de Géographie, 21:120, 1912 p. 462 [↩]

- Ibid p.464 [↩]

- Robequain, Charles, ‘Le climat de l’Indochine française’ Annales de Géographie, 39:222, 1930, p. 653 [↩]

[3]

[3]