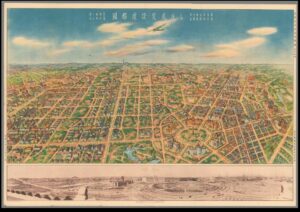

An authoritative score of road networks spans out in front of us; a pleasingly rectangular stamp on a colourful blue-sky background. This is Shinkyo. But if we adopt Michel de Certeau’s argument that a bird’s eye view of a city is inadequate and instead search for the spatial “acting out” of the city, does the “tour” of Shinkyo correspond with its “map”?[1]

In 1932, the Japanese developed a planning proposal which saw the Manchurian town of Changchun transformed into the visionary city of Shinkyo (also Xinjing) and represented the zenith of Japanese industrialisation and competition with the West. The city was developed closely in line with the ideals of the Japanese Guandong Army who had occupied Manchuria, and who prioritised state planning, economic domination, and a unified and obedient public.[2] The proposal included regular street layouts, European-style squares, parks, grand central buildings, and industrial domination. Notably, these developments occurred alongside the increasing importance of the South Manchurian Railway (SMR) which was imagined as the vehicle which would propel Shinkyo into a modernity beyond the access of the West.

The map (see below) was published in 1936 by the State Capital Construction Bureau of the State Council of Manchuria.[3] It is a bird’s eye view of Shinkyo, showing the construction plan with detail of individual streets, monumental centres, railway lines and shrine complexes. It is accompanied by a photographical print of the building progress on the city to that date. The publication of this map by the State Council is valuable in revealing the ideology of spatial reconstruction in Manchuria. The map is striking for its obvious grid pattern. Goto Shimpei, the SMR’s first president and contributor to the planning proposal for Shinkyo, was influenced by European city planning in Germany and subsequently introduced the idea of wide streets and zoned areas according to commercial, residential or commemorative function.[4] The map enhances the impression of this functional zoning by elevating the viewer so that the grid pattern is more pronounced and we adopt the view of the planner or architect who works on the landscape as if it is an operational subject. It implies that the planned vision of Shinkyo was developed independent of the realities of the Manchurian landscape or environment- the plan is flat, the planner has had no need for confrontation with mountains or freezing temperatures. Indeed, the grid pattern on the map fades off to the edges, where the landscape continues as a flat, blank canvas. Historians have categorised this as the utopian “blank page”, planning that only existed on paper.[5] It reveals the desire of Japanese authorities to spatially reconfigure a previously Chinese space into a new centre of Japanese modernity and industrialisation, without any cultural or social challenges. It suggests that city planning during the early 20th century adopted a unique “space-time conception”, where physical construction of roads, monuments and shrines could inaugurate a new era of progress that only Japan could access.[6]

This utopian vision of the future is seen in the detailed features of the map- uniform illustration of housing and additions of minute, unspecified people. This artistic representation disseminated as propaganda suggests that the planners had “free reign of creative vision” and did not include the reality of social structures within the lived city, a vision which filtered down into popular conception of Manchuria. It is true that the uniformity of their plan in some ways translated into reality. Shinkyo did become a hugely efficient commercial centre as the designation of certain spaces for economic and agricultural activity meant that the connective function of the SMR could be fully exploited, for example in the expansion of the soybean trade.[7] However, the static uniformity of the plan does not equate to the reality of 20th century Xinjiang. Even the photograph, evidenced alongside the drawing of the map as if to ratify the existence of the hexagonal dream, is taken before people are included into the equation of the city plan. The uniform housing excluded the presence of the Chinese, who were designated as the enemy, and consequently disrupted the utopia with the erection of immigrant houses on the outskirts of the city. This diverged from the Japanese-style housing and temples assigned on the map. Moreover, cottage industries (largely run by the Chinese) prospered, alongside the domination of the Chinese in banking and moneylending. A tarnish to the vision of a collective Japanese modernity. The map’s neglect of Chinese and Russian commercial districts is compounded by the tiny brushstroke figures we see pounding the streets. They are orderly and unidentified- they pose no social or nationalistic threat to the new Japanese modernity as they are all the same.

The lofty birds eye view of the map, whilst not representational of reality, is valuable in its suggestion of Japanese planning as a means to “scientifically manag[e] energy” in the newly acquired territory of Manchuria to create a distinctly Japanese space.[8] Whilst De Certeau rejected the engineered “concept city”, in the study of 20th century Japan, it becomes valuable for its insight into social and political aspirations.[9] City planning often involved the rejection of real forces of social and environmental change, but created an entirely new space in the administrative imagination- an uninhabited utopia where order and dominance could be asserted through spatial categorisation and management.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Manshukoku Kokumuin Kokuto Kensetsukyoku, Kokuto Kensetsu Hansei Chikashi (Map of Shinkyo), (China 1936).

Secondary Sources

De Certeau, Michel, The Practice of Everyday Life, (California 1985).

Esherick, Joseph, “Railway City and National Capital: Two Faces of the Modern in Changchun”, in Joseph Esherick (ed.) Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950, (Hawaii 2000), pp.65-90.

Tucker, David, “City Planning Without Cities: Order and Chaos in Utopian Manchukuo”, in Mariko Asano Tamanoi (ed.), Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire, (Hawaii 2005), pp.53-82.

Young, Louise, Japan’s Total Empire: Manchuria and the Culture of Wartime Imperialism, (California 1988).

[1] Michel De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, (California 1985), p.98, p.118.

[2] Joseph Esherick, “Railway City and National Capital: Two Faces of the Modern in Changchun”, in Joseph Esherick (ed.) Remaking the Chinese City: Modernity and National Identity, 1900-1950, (Hawaii 2000), p.65.

[3] Manshukoku Kokumuin Kokuto Kensetsukyoku, Kokuto Kensetsu Hansei Chikashi (Map of Shinkyo), (China 1936).

[4] Esherick, “Railway City”, p.74.

[5] David Tucker, “City Planning Without Cities: Order and Chaos in Utopian Manchukuo”, in Mariko Asano Tamanoi (ed.), Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire, (Hawaii 2005), p.60.

[6] Tucker, “City Planning Without Cities”, p.63.

[7] Ibid, p.70.

[8] Esherick, “Railway City”, p.81.

[9] De Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, pp.95-6.