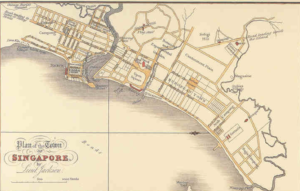

This blog post will focus on investigating how the British colonial powers used urban planning, specifically wide and straight streets, as a form of social control and a way to impose colonial rule. Robert Home’s chapter ‘Planting is My Trade: The Shapers of Colonial Urban Landscapes’ in his book Of Planting and Planning the Making of British Colonial Cities explores how the wide, straight street was a way to impose colonial order upon indigenous culture.1 Home emphasises how, in the 20th century, there was a need to protect colonial cities across the empire against ‘encroachments’ and the British colonial powers saw the ‘straight street’ as a way of more easily detecting and preventing these ‘encroachments’.2 It was such an embedded part of colonial urban planning that street widths were specified in regulations and main roads had a mandatory width of 30-45m.3 This practice of wide and straight streets is evident when examining the primary source of The Jackson Plan for Singapore.4 The plan includes almost exclusively straight streets dividing the city illustrating Jackson aimed to segregate each segment of society to prevent any ‘encroachment’ from banding together and threatening colonial rule. There are also clear divisions for each sector of society, such as the ‘European Town’ or the ‘Chinese Champong’, again allowing the colonial rulers complete control and surveillance of areas that could create resistance. The colonial rulers justified these significant divisions on public health grounds. However, this justification is dubious through examining the traditions of the indigenous population living in Singapore. The indigenous cultures that had lived in the tropics had always favoured narrow streets as they were better suited to the climate. As Home evidences, ‘The Spanish Law of the Indies stated that ‘in cold climates the streets shall be wide; in hot climates narrow’.5 This knowledge had previously enabled the indigenous population to live in Singapore successfully; thus the colonial powers choice to ignore this knowledge illustrates that their justification for the wide roads as a public health measure when tactic to disguise their overarching goal of social control.

Plan of the Town of the Singapore, Lieut Jackson, Survey Department Singapore, Survey Department Singapore (London, 1828).

In comparison, the same use of the straight and wide street can also be seen in the colonial cities of Bombay and Calcutta. In Bombay, the Bombay City Improvement Trust controlled development, made new streets, and opened out crowded areas. One of their key projects was the widening of Church Gate Street from 9 to 21 metres.((Robert K. Home, “Port Cities of the British Empire: A Global Thalassocracy,” in Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), pp. 64-91, 84.)) They also built straight streets to divide the ‘White Bombay’ and ‘Indian Bombay’ as a way to prevent and deter any indigenous opposition.6 Next, in Calcutta, an improvement committee was assigned to ensure that ‘the streets and lanes […] should henceforth be constructed with order and system’.7 The image below shows the imperial capital, and evidences the wide streets that were erected throughout the city in an attempt to keep populations apart. The importance of the layout of these colonial cities and the emphasis on using the streets to ensure ‘order’ again highlights how the British colonial powers were using the city landscape to control the colonised people.

The Central Townscape of Calcutta c. 1930, From A. J. Christopher, The British Empire at Its Zenith (London: Croom Helm, 1988).

Overall, from observing the street layouts in the above maps and images from the colonial cities, Singapore, Bombay, and Calcutta, in the context of Home’s argument the role of the wide straight street becomes clear. It is evident this design was used across the empire as a way to control public space to separate and dismantle societies that could have threatened colonial power. Despite the widening of the streets going against indigenous knowledge of climate control and destroying indigenous spaces, the goal of colonial order and control took priority over resolving any of the hardships caused.

- Robert K. Home, “’Planting Is My Trade’: The Shapers of Colonial Urban Landscapes,” in Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities ((New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2013), pp. 38-63, 61. [↩]

- Ibid., 59. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Lieut Jackson, Survey Department Singapore, National Archives of Singapore (London, 1828). [↩]

- Home, ‘Planting is my Trade’, 61. [↩]

- Ibid., 68. [↩]

- Ibid., 71. [↩]