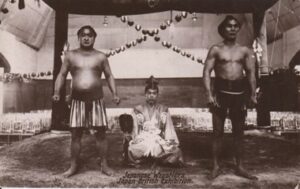

An unwitting visitor to White City, London in 1910 might have received a shock as they turned the corner of Commonwealth Avenue to find themselves faced by flowering rows of cherry blossoms, glistening water fountains, Japanese shrines and half-naked sumo wrestlers approaching their personal space at disturbingly breakneck speed. However, providing they had not been knocked over, with over eight million visitors in attendance across the summer, it should not have taken our unsuspecting guest long to realise they had stumbled across a rather significant exhibition. That being the Japan-Britain Exhibition of 1910 and the largest international expose of culture, technology and status the Japanese Empire had ever been involved in.

Ayako Hotta-Lister has produced a comprehensive summary of the landmark event in her ‘Gateway to the Island of the East’, however, this article is principally concerned with the exhibition’s political objectives and outcomes for the Japanese Empire. By this time, world’s fairs, expositions and exhibitions had become a familiar sight around the world. European and American cities began hosting them frequently from the middle of the 19th century. They became hubs for cultural exchange, global interaction and economic networking. Hotta-Lister has maintained that holding an exhibition ‘became one of the obligatory tasks for a country that had already achieved world power status, as well as for those aspiring to do so’.2 In light of this, and indeed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance signed in 1902, there was seemingly much to be gained and little to be lost by a Japanese Exhibition in London.

Hotta-Lister’s article is a valuable source in understanding the reasoning behind Japan’s desire for an exhibition in 1910. Its objectives, largely instigated by Foreign Minister Komura Jutarō and Katsura Tarō, were ‘principally commercial’.3 Primarily, the two men felt compelled to strengthen trade links, specifically increasing the number of Japanese exports which reached the British Isles.4 Such an exhibition would act as a ‘shop-window’ for Japanese goods. Furthermore, another key objective was to obtain loans from London’s big financiers. At a basic monetary level, the exhibition provided a platform to prove Japan’s transition to modernity and convince creditors that Japan was a ‘good bet’. The opportunity to reinforce the newly formed alliance was also low hanging fruit which the organisers could also not refuse. It is interesting to note that the very name of the exhibition places ‘Japan’ before ‘Britain’, uncommon for this era of British pre-eminence, underlining that the event would take place with the two nations on equal footing.

Ultimately, how successful were the Japanese authorities in fulfilling their objectives in 1910? Firstly, from the point of view of the British, the event was far more popular with visitors than was expected. The attendance was ‘far exceeding the attendance at the Franco-British Exhibition of 1908… one of London’s most successful and popular exhibitions of the decade.’5 Despite this, however, Hotta-Lister’s article reveals that in relation to the Brussels International Exhibition, happening concurrently, the British attitude to the Japan-British event was somewhat ‘lukewarm’.6 Moreover, there was a school of thought amongst the British in certain circles that the event and its exhibits were to an extent uncivilised and unsightly. However, the consensus appears to be that the ‘indifference’ or lack of interest in the exhibition was not widespread amongst the British public and indeed the spectacle was generally enjoyed.

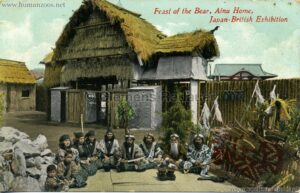

From a Japanese perspective, however, the reactions to the exhibition’s success appear to be more mixed. Whilst Japanese authorities felt it was a top priority to portray an affluent, modern and prosperous image to their British allies, there were many that felt this had not been captured in the exhibits. One such case was the feeling that the village-space that had been constructed was more akin to a poor, rural community than the urban centres which were becoming the centre for modernisation and transformation. The postcard below captures not only the architecture that reveals this, but also the attire and practices of the Japanese participants themselves. This is especially problematic when one considers Timothy Mitchell’s argument that visitors were ‘participant observers’ and active in the scene themselves.7 As such, they would have felt they were ‘there’ in Japan, however the Japan that was depicted was not the modern one they intended to portray.

In collaboration with the sense the ‘wrong’ Japan was represented, there also seems to have been a sense in the Japanese newspapers of the time that ‘exoticism’ and ‘orientalist’ imagery had been played up to. Whilst a fundamental aim of the exhibition was to correct misconceptions of Japanese culture and traditions, entertainments such as the Sumo wrestlers, in ‘authentic near-naked splendour’, were seen by many as ‘novelty’ and certain visitors found it offensive and as further evidence of Japan’s ‘backwardness’.9 Japanese commentators found this aspect of the exhibition self-demeaning, rather than image-enhancing.

In conclusion, exhibitions such as the Japan-British of 1910 are clear platforms for the demonstrating of success, modernising and cultural affluence. Whilst the exhibition was widely attended, generated attention and stimulated economic collaboration between the two nations, the general feeling among Japanese stakeholders was that it fell short in creating ‘soft power’ and promoting Japan’s image. It was successful in being educational about Japan’s culture, norms and practices, but appears to have lacked clarity when expressing Japan’s transformation into a world-leading political entity. A missed opportunity? Perhaps. One only has to compare such an exhibition to an extravagant event like Dubai’s Expo 2020 to realise that Japan could perhaps have done more to concentrate its efforts on displaying its status as a big player on the geopolitical stage.

- https://i.pinimg.com/originals/ea/dd/3f/eadd3f07ff5f797222f66528adb1527f.jpg [↩]

- Ayako Hotta-Lister, The Japan-British Exhibition of 1910: Gateway to the Island Empire of the East, p. 4 (London, 2000) [↩]

- Hotta-Lister, The Japan-British Exhibition of 1910, p. 74 [↩]

- Ibid [↩]

- Ibid, p. 111 [↩]

- Ibid, p. 110 [↩]

- Timothy Mitchell, ‘The World as Exhibition’ in Comparative Studies in Society and History, 31(2), (1989) p. 231 [↩]

- 1910 Japan-British Exhibition – Human Zoos [↩]

- Hotta-Lister, The Japan-British Exhibition of 1910, p. 118 [↩]