“The exhibition persuades people that the world is divided into two fundamental realms – the representation and the origin, the exhibit and the external reality, the text and the world.”1

—- Timothy Mitchell

According to Timothy Mitchell’s “The World as Exhibition”, the world in the exhibition is a distinct realm from reality. This phenomenon does not only exist in a metaphorical sense but also occurs literally in real life. In the 1910 Japan-British Exhibition, in order to recreate a vivid and realistic experience for the visitors, many minorities from native Japan and from Japanese colonies were asked to participate in this joint exhibition. They were Formosans, Sumo wrestlers and Ainus.2 Among them, Ainus had a distinct situation from the other two. Compared to Sumo wrestlers, the Ainu people were more distant from the mainstream Japanese culture, led by Yamato Japanese people. Compared to Formosans, Ainus are not from the colonies of Japan, they are also native Japanese people. The territory of Ainu had been under the control of Yamato Japanese for a very long time since the Tokugawa period.

As David Howell states that the traditional way of living of Ainus was inevitably disrupted by the intrusion of the modern lifestyle promoted and popularised in the Meiji period. For example, In the mid-1880s, officials in Sapporo and Nemuro prefectures attempted to turn Ainu into farmers and then integrated them into the general Japanese population.3 Homogenization of the Ainu people was a part of constructing Japan as a modern state. Hence, until 1910, Ainus had been going through this process of assimilation for about thirty years. In contrast to what happened in the homeland, the indigenous people in oversea exhibitions always appeared with strong indigenous characteristics. There was a paradox that existed between the foreign diplomatic and the domestic policy, which targeted the indigenous people. The presence of Ainus in the Japan-British exhibition was a typical case and example of this paradox. In the case of the Ainu people in the foreign exhibition, this paradox created by the contradiction between the foreign and domestic policy of Japan reveals the ambition of Japan to claim its new status as a rising imperial power which had the potential to rival western countries in the international arena and its eagerness and rashness to do so in the early twentieth century.

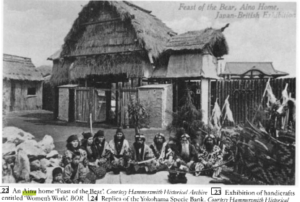

Figure 1: Postcard of Japan-British Exhibition

Ainu people are the indigenous people of Hokkaido, southern Sakhalin, and Kuril Island. They had a very intimate relationship with the general Japanese population but were also able to maintain their own uniqueness. Figure one is the postcard printed for the Japan-British Exhibition. In this postcard, there was a group of Ainus sitting in front of a traditional Ainu house. All of them wore traditional costumes, including robes and headbands. It was not the first time that Ainus were sent to participate in an exhibition. They also participated in the St Louis exhibition in 1904.4 According to the photo on the postcard, it could be observed that Ainu’s cultural and daily life characteristics were magnified and condensed in this scene. The construction of the hut and the dress of the Ainus people were all representative symbols of Ainu. According to the word of John Batchelor’s words quoted by Hotta-Lister, an Ainu man in the exhibition warmly introduced visitors to their customs and traditions.5 However, it was only under the condition that John Batchelor was able to translate Japanese for the other visitors, thus the main purpose of having native people was to create a visual effect for the audience, rather than hiring them as guides. The point was that the visitors could actually see and observe them with their own eyes, to educate themselves about Ainu customs and traditions. It is very similar to what Timothy Mitchel has found in the writings of Arabic writers in Paris. The enhancement of Ainu elements in the exhibition seems to contradict the domestic policy of Japan towards Ainus which aimed to integrate them into the general Japanese population.

The paradox caused a debate on the exhibition of the Ainu people in foreign countries. Hotta-Lister mentioned that this 1910 exhibition aimed to show Britain that Japan is a powerful nation which is worthy of making allies with and to clear the misunderstanding the public had on Japan.6 The exhibition of Ainu should be used as evidence of Japan’s backwardness so that visitors could have an object of reference to the new modern and advanced Japan.7 The magnified traditional Ainu elements in the exhibition could prove this point. However, the domestic reaction to this joint exhibition criticized that the presence of these backward races did not send a positive message about the Japanese empire to the general visitors. One word used by Hotta-Lister to describe the feeling experienced by the other Japanese is “embarrassment”.8 The reaction of the British was also not positive. The exhibition of indigenous people brings out the question of human rights and the debate on racism.9 Then the exhibition of native and indigenous culture became an awkward existence at these fairs. On the one hand, they could not represent the ‘authentic’ appearance of Japan; and on the other hand, its existence does not work in the way which people thought it would. In Mutsu Hirokichi’s article written to introduce the exhibition, the exhibition of Ainu was not even mentioned once.

Following the theory of Mitchell, the paradox that existed in the exhibition of the indigenous culture of the Ainu people could be explained that the world of the Ainu people in the exhibition is a different reality from that of in Japan. The paradox also exists on an abstract level that the world exhibited is contradictory to the world in the reality. As mentioned above, Ainus were going through the process of assimilation with the general Japanese population, and in the narrative of John Batchelor, the Ainu man who was explaining their tradition to them could speak Japanese fluently, thus Ainus who were part of the exhibition may not continue or follow their traditions as the exhibition shown. The life they exhibited to the general visitor was a created reality, specifically for the purpose of exhibiting.10 The exhibition also generalized the actual life of the Ainu people in Japan, ignoring the fact that there were many subdivisions of the Ainu people and each of them led different lifestyles. Both in real life and the exhibition, the customs, traditions, and everyday life of Ainu are reshaped. Ainu culture and people presented in the exhibition are intended exoticism, a world of representation, designed to justify the imperial mission of Japan and its power as a rival colonist. The domestic policy of assimilation also serves the purpose of consolidating imperial rule. These contradictions and the logic behind the exhibition of Ainu which can’t stand scrutiny reveal the eagerness of the Japanese empire to demonstrate its equal status with the other western countries.

- Timothy Mitchell. ‘The World as Exhibition’. Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, no. 2 (April 1989), p. 233. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 229. [↩]

- David L. Howell, ‘Making “Useful Citizens” of Ainu Subjects in Early Twentieth-Century Japan’, The Journal of Asian Studies, 63.1 (2004), pp. 6-7 [↩]

- Hotta-Lister, A. The Japan-British Exhibition of 1910: Gateway to the Island Empire of the East. 1 edition. Richmond: Routledge, 1999, p.117. [↩]

- Ibid, p.144. [↩]

- Ibid, pp. 110-111. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 142. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 143. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 133. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 144. [↩]