The British Museum has a surprising amount of space dedicated to Asia, and specifically China – aside from sections devoted to Chinese jade and its products, and a rather extensive and well cataloged section devoted to Chinese porcelain, there is a section devoted to the region itself. While the fact that entire sections are dedicated to Chinese jade and porcelain is in itself worth examining from a spatial standpoint – ascribing a large degree of focus on the categorization of these singular types of items – what is especially interesting is the framing of the Chinese history section around Buddhism.

Green, Brendan. Overview of the Gallery of China. September 2, 2023. Photograph, 4032×3024 pixels.

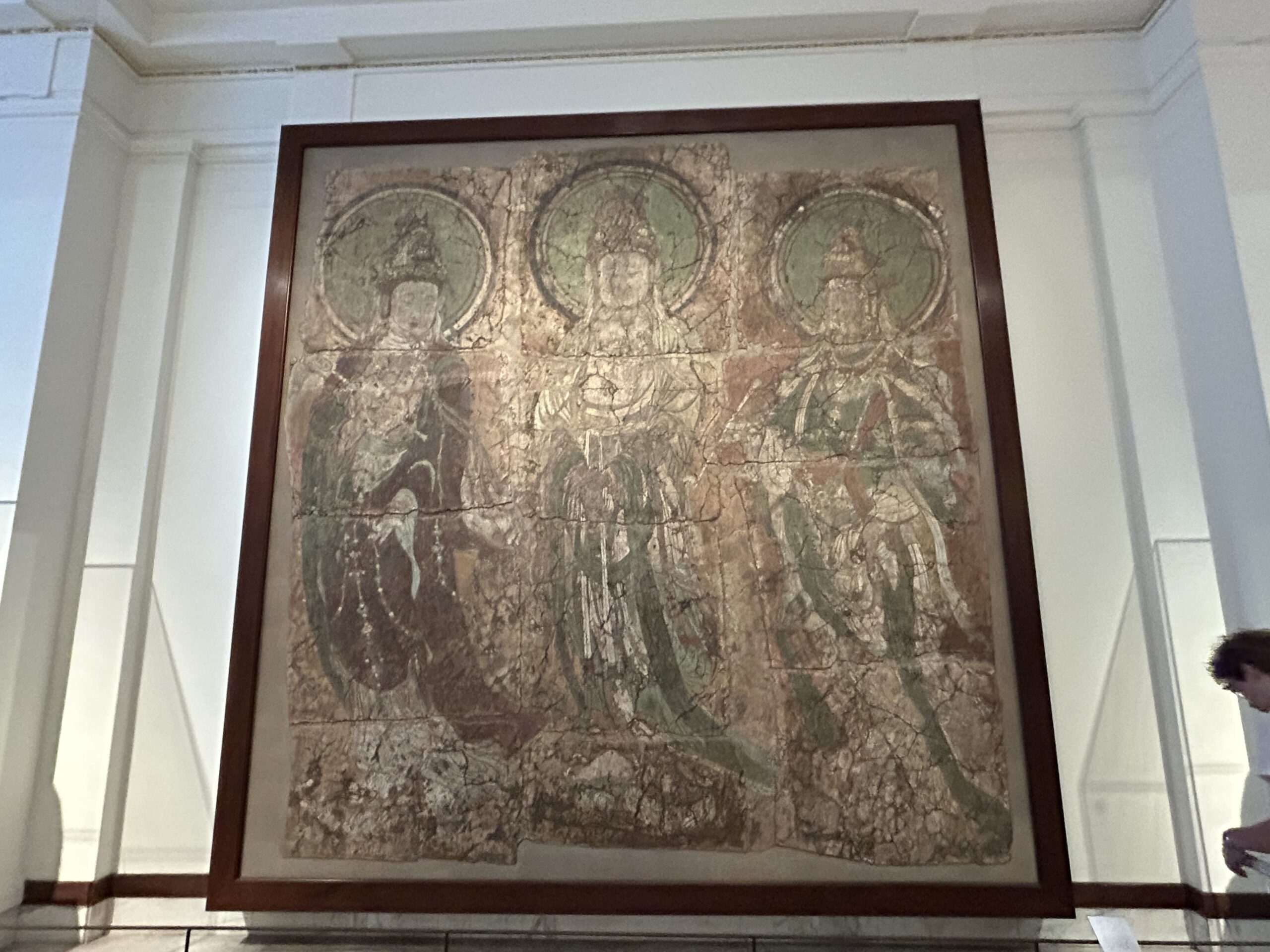

The initial view of the section as one enters it is striking – red pillars flow from the front to the back of the area, separating the different subsections. The impression is almost like that of a temple – something that is strengthened by the display in the far back and center of the section. The display is that of three Bodhisattvas overlooking the entire area, dwarfing most of the exhibit physically. If there is a visual narrative created by the spatial layout of the section, it is one that places Buddhism at the center of Chinese history.

Green, Brendan. Three Bodhisattvas Overlooking the Gallery. September 2, 2023. Photograph, 4032×3024 pixels.

The subsections of the area also place an emphasis on Buddhism – for the most part, these sections divide China along temporal lines, by constructions such as ‘early’ and ‘modern’ China, and along dynastic lines. One of the few exceptions to this is the subsection completely devoted to Buddhism in China.

Green, Brendan. Structure of the Gallery of China. September 2, 2023. Photograph, 4032×3024 pixels.

The focus that the section places on Buddhism is noteworthy because while Buddhism is important in Chinese history, it is far from the most important or only element in the history of Chinese religion, culture and spiritualism. Taoism and Confucianism go nearly unmentioned throughout the entire section, while displays that contain artifacts relevant to non-Buddhist religious and spiritual practices are discussed outside their respective contexts.

It is difficult to ascertain exactly why the British Museum decided to frame its China exhibit around Buddhism. One possible reason is due to material limitations – perhaps the Museum simply did not have access to as many artifacts related to Taoism and Confucianism as they did Buddhism. Perhaps the Museum decided that centering the section around the display of the three Bodhisattvas would make for a striking and dramatic image, and themed the section to match. Regardless, it is an interesting example of how a museum can construct narrative through spatial arrangement.