‘It probably would be safe to bet that more people take pictures of cherry blossoms than any other subject in Japan – but of all the millions of pictures captured, only a small percentage capture the subtle beauty on film. ‘1

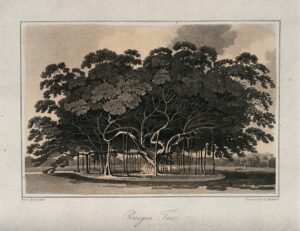

The space which Cherry blossoms occupy is difficult to categorize because of its temporality. Therefore, springtime in Japan has become a favourite time for tourists to visit the country and flock around cherry blossom trees in full bloom. As a consequence of the cherry blossoms’ appeal to both tourists and the Japanese, many of the spaces which these trees occupy have become public spaces such as parks and pedestrian routes. Despite modernity taking over and urbanizing Japan, sacred parts of nature have ensured that modernity has had to be built around them, rather than over them. This is similar to the alun-alun in Malang, which is a large space occupied by the banyan tree. The alun-alun holds similarities because the sacredness of the banyan and the beauty of the cherry blossom ensuring that these spaces cannot be remodelled into a product of modernity. Not only that, but the act of cutting down these types of trees was and still is associated with superstition and uneasiness. Therefore, tourism and superstitions have aided in the progress of creating these green spaces into a social setting in which tourists or locals could benefit from.

However, much like the alun-alun in Malang, there is difficulty in defining what the spaces in which trees such as the Banyan and cherry blossom occupy are. The people who gather in these spaces are not there to primarily consume or socialize, but as a result of planting such trees, products of consumption and space for socializing are created. Therefore, defining such spaces becomes complicated due to the conflictive uses of the space. Without the cherry blossoms, these spaces become pathways, parks, and green spaces, but the temporality of the trees allows these spaces to transform into a place to consume, observe, socialize, and entertain.

Although the alun-alun is different in its purpose, the banyan tree aids in how spaces can be defined differently depending on how it is used. ‘The banyan tree, which was once considered sacred in the context of Javanese culture, was deprived of its aura as the crowd of modern-day tram passengers used it casually as a tram shelter.’ 2 Therefore, what the banyan tree provides is a safe place for indigenous Javanese to step out of the exclusiveness that westernization has brought to society and seek sanctuary under the banyan trees in the alun-alun. Sacred attachments to nature allow spaces such as the alun-alun and those which cherry blossom trees occupy, to strengthen the cultural value which modernity has threatened.

‘However, if the indigenous people could not take part in the colonial social activities inside the buildings surrounding the alun-alun, they could at least defy the Western life-style.’3 Furthermore, this ability to escape into a space that functioned outside of westernization and modernity was aided by the banyan trees which allowed not only shelter but a connection to culture and history that was being overshadowed by a changing society. Although this is perhaps an environmental factor, the trees construct how a specific space can be used for social and leisure means.

‘In Hindostan, where it reaches the greatest perfection, a famous tree stood on the banks of the Nerbudda. It was said that formerly 7,000 men could find shelter beneath its shade.’4

The result of this has meant that urbanisation has had to be shaped in a way that accommodates trees such as the cherry blossom and Banyan because they are rooted into local culture and history. In cases such as the banyan, superstition has protected them because of the act of cutting it down being to risky. Therefore, enabling a unique space to be formed around them. However, in terms of the Cherry blossom, there are multiple factors which have enabled their survival, which are centred on culture and tourism.