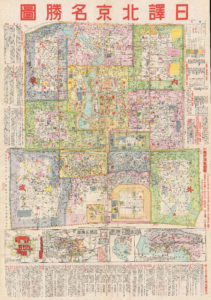

Figure 1. Beijing 1930 Chinese City Map or Plan of Beijing (Peking), China.

The city of Beijing has been the capital of imperial China since the Yuan dynasty. The map shown above was produced in 1930 by the Japanese. It portrayed the old urban structure of the Beijing city. The map consists of several rectangular blocks named 舊紫禁城 (the Forbidden City), 舊皇城 (the Imperial City), 內城 (the Inner City), and 外城 (the Outer City). The Forbidden City and the Imperial City were contained in the Inner City. The textual explanations provided on both sides of the map are about the categories of the marks on the map. Such details contribute to the analysis of the old urban spaces of Beijing. Through a meticulous examination of the map, accompanying the secondary materials in this week’s reading list, the blog posits that the historical urban layout of Beijing expresses a critical essence of the imperial authority: the manipulation of human mobility and activity. The imperial ruler utilised his authoritative power to regulate the mobility of the general populace in Beijing by arranging fixed residences for specific groups, and to restrict human activities by introducing social rules in different areas of the city.

First, the urban blocks of old Beijing required and designed by the imperial government mentioned above resulted in the segregation of different groups of people. For instance, on the map, the green part represents the residential location of famous individuals 著名處所. Most green parts on the map are in the Inner City, with only small parts found in the Outer City. According to Dong Madeleine Yue, the Inner City was the residence quarter of the “Manchu aristocrats and high officials”[1] as well as the “banner men and their families, who were responsible for guarding the palace and defending the capital.”[2] It is evident that the green parts in the Inner City belonged to influential nobility-related figures of the Imperial era. Yet, the residents of the green parts of the Outer city were different, especially in the Qing dynasty (1636-1912). Dong notes, “when the Manchus entered Beijing, they banished Han residents from the Inner City.”[3] It therefore can deduce that the small green parts of the Outer City mostly belonged to well-known Han figures as these people could not live in the Inner City. The ordinary people who did not play an important role in the imperial system were not allowed to be the residents of the Inner City. This division of the residence was not initiated by the ordinary people themselves, but rather imposed by the imperial authority. This resulted in the confinement of the ordinary to certain areas, shaping relatively fixed settlements for different groups of people and making the ordinary keep in captivity like livestock. The imperial administration at this moment manipulated human mobility and controlled the should-be division of people in Beijing by allotting the land to its residents.

Furthermore, the blog claims that the imperial manipulation of the urban design of the Outer and Inner cities contributed to the development and emergence of the theme zones. These organic parts in the urban area combined as an organic whole to support the entire imperial Beijing. The commercial area in the Outer City is a great example. When zooming in the map, it is hard to see the shops and stores directly associated with commercial activities within the Inner City. In contrast, in the Outer City, many shops of different categories are shown, such as 葱店 cong shop, 文宝楼 wenbao building, 纱纸坊 gauze paper shop. It is because that “no permanent businesses, guilds, or forms of entertainment were technically allowed in the Inner City,”[4] according to Dong. This situation was a product of the imperial strategy and manipulation. Dong once depicts the bustle of the Outer City’s business district: “the northern part of the Outer City was the bustling and prosperous commercial center for the imperial capital.”[5] Even if it did not designate the Outer City as an area with prosperous commerce, the arrangement of the Inner City urged development of the business in the Outer city as the Inner City could not “serve the daily needs of its residents,”[6] as Dong notes. The Inner City under the imperial control was a city without a synthetical life. In this case, the Outer City had to develop areas and social occasions to fill in the gaps in the Inner City living areas.

Overall, this blog intends to demonstrate the nature of imperial authority – the control of human mobility and activities. The separated blocks made up by imperial manipulation resulted in the segregation of ordinary people in designated locations. The imperial authority was the decisive agency in this process. As for the limitation of human activities, the urban spaces designed by the imperial government urged the development new areas and social occasions in the Outer City, the commercial area in particular. Such an area was an integral part of the efficiently functioning organic whole. However, the overall logic of constructing this organic whole was determined by the supreme control of the imperial authority, rather than the spontaneous generation of the ordinary people. Therefore, the urban plan of the city of Beijing was a manifestation of capability of the imperial authority rather than the human initiative.

[1] Madeleine Yue Dong, Republican Beijing: The City and Its Histories (Berkeley, 2003), p. 27.

[2] Dong, Republican Beijing, p. 27.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.