The planning of Manchukuo (滿洲國) was an articulation of “utopia” for Japanese urban planners and architects, an empty canvas upon which Japanese architecture and construction could project a “Japanese” technical superiority. Historians have shown how planners manifested this in “modern” technologies relating to water supply, heating, sanitation, residential infrastructure.1 Yet, planners increasingly needed to accommodate the Japanese vision of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Within the spatial logic of Manchukuo, however, this latter vision was constricted by the planners’ own implementation of space in Manchukuo. The 16-17 September 1937 commemoration of the completion of capital construction that was meant to legitimise Japanese imperialism, I argue, demonstrates how the former unwittingly undermined the latter.

Images are from Yishi Liu’s Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-19572

Firstly, the September commemoration was a deviation from the original, central concern of the colonial authority of planning Changchun. The founding of Manchukuo had been 1 March 1932, but authorities reflected that an anniversary celebration in March 1937 was too early for uncompleted infrastructure. Hence, a modest, barely publicised celebration was first held in the capital Changchun to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the establishment of Manchukuo. Correspondingly, the September commemoration of the construction of Changchun encompassed a working group and preparations including “siting, constructing temporary buildings, deciding the agenda and participants, security, propaganda, and above all, the tour of the emperor. The total cost for the ceremony reached 149,565 Yen.”3

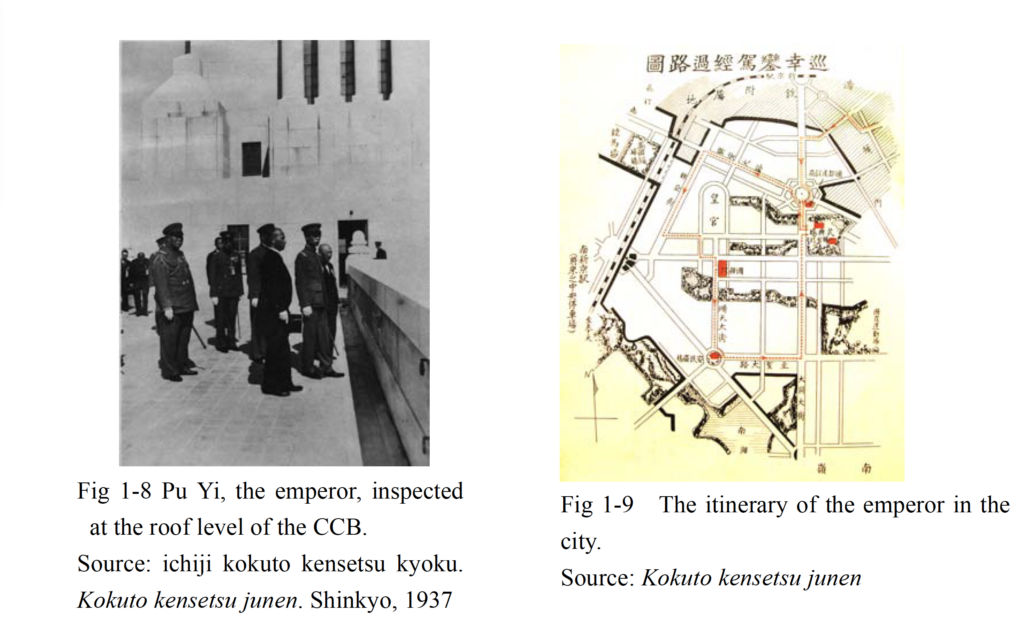

Critically, we should see the remit of the emperor Pu Yi as a fascinating tale of exclusion. The puppet emperor’s significance had been spatially obvious from the get-go – Pu Yi had been housed in what was ‘far from being the grandest house in the city’.4 Yet, even as Pu Yi still retained a ceremonial role, the government-organised tour focused on the legitimising of physical infrastructure over other aspects of governance. Pu Yi’s itinerary consisted of the Capital Construction Bureau (CCB), Datong Plaza, State Council and exhibits of State Council construction achievements among others. At the end of the day, Pu Yi then returned to the palace while officials had a dinner banquet together.5

Liu further demonstrates that the September celebrations were augmented by copies of the emperor’s itinerary, a parade procession that was popularly attended, and the selling out of commemorative memorabilia. Finally, on the 17th, the bonfire tower at Datong Plaza championed “co-existence and co-prosperity” in an imposing manner where it had been flashing the words 一心一德 (”heart and virtue in unity”). While Liu omits further detail on the mass congregation that followed in the days after, possibly due to source limitations, Liu’s exposition of the pomp of the world fair and the “exhibitionary edifice” critical to the Japanese imperialist project demonstrates clearly the primacy of urban construction to Japanese colonialism in Manchukuo.

By privileging the tenets of utopia that underlined the Japanese construction of Manchukuo, I have argued that even the “fair” or “celebration” in a utopic spatial plan can undermine the original structures of rule undergirding such a spatial arrangement. Here, the utopic priorities of the urban planner took precedence over the symbolism of Japanese control in the first place – the September celebrations demonstrate the primacy of space as a way of asserting Japanese imperialism under the disguise of modernity and material progress under a purportedly Asiatic banner.

- See: David Tucker, “City Planning Without Cities: Order and Chaos in Utopian Manchukuo” in Mariko Asano Tamanoi (ed.), Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire, pp. 53-81. [↩]

- Yishi Liu, Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957, PhD Thesis, University of California, 2011, p. 13. [↩]

- Yishi Liu, Competing Visions of the Modern: Urban Transformation and Social Change of Changchun, 1932-1957, PhD Thesis, University of California, 2011, p. 12. [↩]

- Bill Sewell, Constructing Empire: The Japanese in Changchun, 1905–45 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019), p. 106. [↩]

- Yishi Liu, Competing Visions of the Modern, p. 12. [↩]