How much do urban planners know about the historical contexts of the spaces they organise? In this post, I engage in a rudimentary exploration of oral histories of the Punggol area in north-east Singapore and find that there existed no single historical context to speak of. Indeed, while histories of Punggol were similar to other planned areas in that they were richly variegated along lines of religious identification, dialect and surname association for the Chinese, Punggol inhabitants’ genealogies suggest a different orientation in the first place – that within the wider Malay Archipelago.

Two accounts of urban planning suggested to me the need to seek the perspectives of the proverbial walker. Firstly, Wooldridge’s nuanced and holistic chapter on Zeng Guofan’s image of Nanjing reconstruction demonstrated how literal reconstruction was state building.1 To be sure, Wooldridge’s grasp over the funding and bureaucratic machineries specific to Zeng worked well to evince different power systems when read with Yeoh’s chapter on the municipal government in Contesting Space.2 Here, Wooldridge was well aware of the limits of understanding the urban planner’s logic of reconstruction, noting the complex regional identities for the Nanjing intellectual elite who returned to Nanjing after 1865, even if the chapter eventually contained little in-depth exposition of these nuances.

While that served his point of top-down “reconstruction”, I instead considered Punggol, recently in Singapore the centre of a history exhibition at the opening of its new library. Contemporarily, it is known today as a housing neighbourhood town designed to court young families attempting to purchase public housing flats. Yet, what was this image reconstructed from?

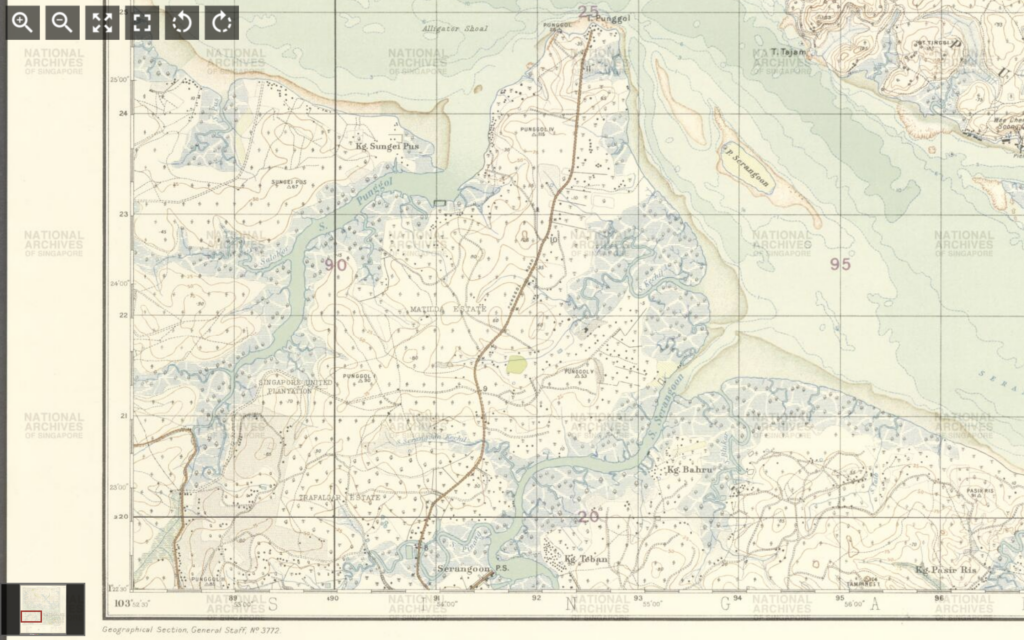

In Singaporean heritage projects, the spatialisation of Punggol has been the particularity of its “Track” system.3 However, when we examine maps from the National Archives of Singapore, the “Track” system first appears only on maps after 1959 – the year Singapore attained full internal self-government.4 Before that, topographical maps of Punggol were produced by the colonial-era Singapore Survey Department. These surveys were fixated on features such as railway widening lines and municipal boundaries. These maps also used the ‘mukim’ system; and between the first maps in the nineteenth century and 1959, little new information was added for each new addition for the focus was on land titles and land use.5

Correspondingly, this gulf is echoed in oral history interviews. On the other hand, oral history interviewees who were born before the 1950s used the Punggol ‘milestone’ markers as their way of spatialising Punggol.6 What remains similar in pre-1959 and post-1959 accounts, beyond the use of property and the association of land with ownership, is the exacting of demographic association down to specific streets for different dialect groups and surnames – a phenomenon Yeoh has elaborated on clearly in Contesting Space.

Yet, another primary source in 1957 presents a completely new dimension to Punggol history. In 1957, Muhammad Ariff Ahmad, a teacher based in Sekolah Melayu Ponggol (Ponggol Malay School), published Tok Sumang, the tale of his great-grandfather. In the English translation7 we learn that Tok Sumang had originated from Pahang and that his family had never been ‘fixed at one place’ – it was in the aftermath of war training on Tekong that he decided to move to ‘neighbouring Singapore, which was covered with dense forests and home to crocodiles and snakes.’ By 1891, Tok Sumang (‘always accompanied by his shovel and violin’) and his followers had agreed with the British that the land would never be taxed in exchange for the British construction of a road – the road that was built leading to the shore of Tanjong Punggol was named “Jalan Wak Sumang”. This was a different location of Punggol, not as an administrative unit in Singapore, and far from the contemporary understanding of the sovereign Singaporean nation-state as the center.

My comparison of Survey Department maps and different recollections of Punggol over time merely scratches the surface. In this case, the Surveyors’ maps did not merely lack markers of local knowledge. Between the Survey Department and internal self-government, topographical indicators said more of each administration’s goals than of Punggol’s historical particularity. The former emphasised land value, while the latter identified features of ‘community’ according to its own understanding, including landmarks such as ‘community centres’ and ‘police stations’. Secondly, the proliferation of a range of historical memories demonstrates one way in which the Lefebvrian idea of the “lived” can be actualised. Methodologically, I argue that there are far-reaching implications in using oral history to challenge the urban planner’s primacy. Oral histories and heritage culture, however state-directed either might potentially be, still spatialise a multiplicity of histories in ways that an urban planner’s map cannot.

- Chuck Wooldridge, City of Virtues: Nanjing in an Age of Utopian Visions, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015, pp. 117-149. [↩]

- Brenda Yeoh, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment, Singapore: NUS Press, 2003, pp. 28–78. [↩]

- https://remembersingapore.org/2018/09/30/old-punggol-road-26-tracks/ [↩]

- Singapore Survey Department, Singapore 1961 – Tampines Accession Number TM000054_3. The use of “Track” is further replicated not just on topographical but electoral maps following this, with the post-1959 maps also taking care to mention vital community fixtures such as community centres and police centres – itself a change that deserves a discussion beyond the scope of this post. [↩]

- The Singapore Land Authority uses the system today, explaining that “Every land parcel in Singapore is uniquely identified by a lot number. This identifier has two components, namely the survey districts Mukim (MK) or Town Subdivision (TS) number and the lot number.” Mukim is a Malay word meaning ‘district’ with its roots from the Arabic مقيم (resident). [↩]

- Lee Chor Eck, Oral History Interview with Chai Yong Hwa Accession Number 000172. https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/oral_history_interviews/record-details/e0d5e6eb-115d-11e3-83d5-0050568939ad?keywords=Punggol&keywords-type=all. See especially reel 3 and reel 7. Maria Boon Kheng Ng, Oral History Interview with Hong Siew Ling, National Archives of Singapore . https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/oral_history_interviews/record-details/f09a160a-115d-11e3-83d5-0050568939ad?keywords=Punggol&keywords-type=all. See reel 3. [↩]

- Muhammad Ariff Ahmad (trans. Ahmad Ubaidillah), Tok Sumang, (Singapore: Geliga Limited, 1957). https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-19/issue-2/jul-sep-2023/tok-sumang-english/ [↩]