A unique and vibrant culture has taken root in the bustling streets of Singapore, whose members are known as Peranakans. The term ‘peranakan’ originates from the Malay word ‘anak,’ meaning child and has come to signify being locally born.1 Yet it crucial to mention the freighted task of defining the term ‘peranakan,’ for their shifting political and cultural dynamics that have come to characterise this community has led to a rich and multifaceted history. In fact, in Southeast Asia there are Peranakan Indians who are Hindu and called Chitty Melaka, as well as Peranakan Indian Muslims called Jawi Pekan, in addition to Eurasian Peranakans and Peranakan Chinese, to name a few.

However, this discussion will focus on the Chinese Peranakans in Singapore. The history of the Chinese Peranakans in Singapore traces back to the arrival of traders from the southern province of China, who settled in the Malay Archipelago. Not only did they establish a trade network, but they married local Malay women. This intermarriage gave rise to a unique blend of cultural practices, traditions and languages.2 After Sir Stamford Raffles signed a treaty in 1834 which led to the establishment of trading posts in Singapore, these traders migrated to Singapore and left an indelible mark on its architectural landscape. The shophouses, bungalows, and mansions they established in Singapore reflected the rich tapestry of cultures and traditions in which the Peranakan Chinese community engaged with throughout their history.3

Indeed, one way to explore the rich history of the Chinese Peranakan community is by taking a closer look at their homes, which also helps reflect a relationship between identity, space and architecture. The Peranakan home is a tangible symbol of the cultural fusion that defines Singapore. These homes are often built with a blend of Chinese, Malay and European architectural influences, which reflect the multicultural fabric of Singapore and the peaceful coexistence of various ethnic and cultural groups. However, there is no architectural style that can be exclusively attributed to the Peranakan Chinese, like the Peranakan people themselves, housing developed with an array of variations each reflecting a specific place, time and economic circumstance in which it was created. Therefore, this discussion will look at the memoir of William Gwee Thian Hock’s whose narration provides an illustration on how identity was forged in their living space. Yet, as one steps into the world of the Peranakan home, it is a complicated space, thus this discussion will also focus solely on the bedroom as an example of how space and identity were harmoniously woven together.

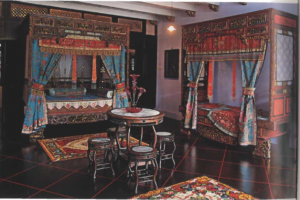

Figure 1. An extraordinary presentation of a bridal suite in a Peranakan home.4

William Gween Thian Hock’s memoir, A Nyonya Mosaic, is set in Singapore in 1910 and narrates the childhood of his Nyonya mother through her own eyes. Throughout there are scenes of happy celebrations, as well as disease and death. Hock’s scenes of a wedding are particularly intricate and colourful, and does well to shed life on the lived experiences in these homes. Moreover, figure 1 helps capture the narrative in Hock’s memoir by presenting a reconstructed Chinese Peranakan bedroom, arranged to recreate the ambiance of a wedding day for the bride and groom. Together, these two sources illustrate a contact zone where a diverse array of cultures intersect and interact.

As stated in Hock’s memoir, ‘the bridal room was on of the focal points’ and as figure 1 illustrates significant preparation and thought had gone into its spatial layout.5. Figure 1 is a striking statement to the intricate beauty that characterises a Chinese Peranakan bedroom. Within this frame, one can witness a unique cultural fusion of Chinese, Malay and European traditions blending together to create a functional space. For example, the two canopy beds display European influence, whereas its ornate carvings are quintessentially Chinese.

Hock notes ‘I was rather taken aback when few days before [the wedding] I discovered that the beautifully carved wooden ranjang loskan would bot be used for the wedding. I have always associated this bed with weddings and there were even people who knew it by the name of ranjang kahwen (wedding bed). It seemed that it was no longer fashionable to use this ornate bed, and in its place, a Victorian four-poster brass bed had been chosen … the embroidered curtain around it, the embroidered bedsheet, the embroidered pillowcases and all thh other trimmings that festooned the bed had transformed it into a most charming wedding bed.’6

Indeed, in figure 1 on closer inspection ornate wood carvings are present and are quintessentially Chinese. For example, one can locate auspicious motifs such as dragons, phoenixes, magpies and mandarin ducks which signify harmony between the marrying couple. Furthermore, another interesting aspect of this bridal suite is the carpet. These rich tapestry-like carpets are referred to as ‘Irish carpets,’ which were produced in factories owned by Scottish textile manufactures in Ireland. They are made of velvet and have a smooth finish with saturated colours. The colours are exuberant, replicating the hues of tropical flowers that are important to Chinese culture.7 This spatial arrangement highlights their diverse identity.

It is interesting to note Hock’s statement that, ‘it seems so unfortunate that a wedding so oriental in flavour should suddenly find a western touch in it just for the pride of being “modernised”‘8 Hock’s statement reflects the disappointment felt in witnessing the groom’s attire change to a western-style lounge suit. But as stated in Elizabeth LaCouture’s influential work Dwelling in the World: Family, House and Home in Tianjin China, 1860-1960, this was a symbol of modernity. For individuals living in a Chinese urban home ‘modernity was not defined through Western and Chinese temporalities and cultures. To be modern meant to be comfortable dwelling in both of these worlds.’9 This perspective is crucial as it shows how such a community navigated their identities in a changing world. Clearly, they drew from their cultural heritage while incorporating aspects of Western culture, not as a contradiction, but as a means of adapting to the complexities of modern, cosmopolitan life.

This brief exploration of a traditional Peranakan wedding and the Peranakan bedroom effectively highlights how this community accepted, adopted and assimilated diverse cultures to form a cosmopolitan community of their own, based on their understanding of the world and conceptions of the modern.

- David HJ Neo, Sheau-Shi Ngo, Jenny Gek Koon Heng, ‘Popular imaginary and cultural constructions of the Nonya in Peranakan Chinese culture of the Straits Settlements,’ Ethnicities, 20:1 (2020), p.25. [↩]

- Patricia Ann Hardwick, ‘”Neither Fish nor Fowl”: Constructing Peranakan Identity in Colonial and Post-colonial Singapore,’ Folklore Forum, 38:1 (2008), p. 37. [↩]

- Roland G., Knapp, Peranakan Chinese home: Art and culture in daily life (2017), p.6. [↩]

- Figure 1, ‘Image of a reconstructed Peranakan bridal suite,’ in Roland G., Knapp, Peranakan Chinese home: Art and culture in daily life (2017), p.142. [↩]

- William Gwee Thian Hock, A Nyonya Mosaic: Memoirs of a Peranakan Childhood, (2013), p. 76. [↩]

- Hock, A Nyonya Mosaic, p. 78. [↩]

- Knapp, Peranakan Chinese home, p.144. [↩]

- Hock, A Nyonya Mosaic, p. 104. [↩]

- Elizabeth LaCouture, Dwelling in the World: Family, House and Home in Tianjin China, 1860-1960, (New York, 2021), p. 153. [↩]