In 1906, a delegation of court officials returned to Beijing from Germany with a host of exotic animals. The lions, tigers, zebras, and elephants they brought back were placed on imperial land, and thus the Garden of Ten Thousand Animals, or Wanshangyuen, was born. Two years later, it would open to the public, charging sixteen coppers for adults and eight for children.1 While this was an unprecedented space in China, similar zoological parks had been present in Asia since the mid-nineteenth century. The first was established in Batavia in 1864 and another followed soon after in Singapore in 1875.2 However, though they were superficially similar spaces to the Wanshengyuen, Beijing’s zoological park took on extra cultural meaning due to the historical context it arose in. While the Singapore and Batavia zoos existed within a colonial framework and thus served to perpetuate the existing colonial regime, the Wanshengyuan was used as a tool to herald a new urban age for Beijing.

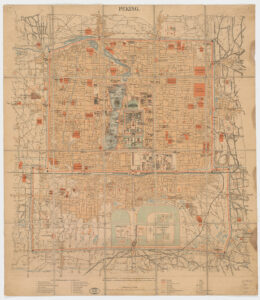

Figure 1: Map of Beijing 19033

The Wanshengyuan was located just outside the walls to the Inner City, built on land which had previously held two imperial temples and their gardens. This space is visible in Figure 1 in the top left corner, labelled “Garten der Wohltätigkeit”. Since the fourteenth century, the city of Beijing had followed strict spatial delineations, with concentric walled segments dividing people by class and status. The Forbidden City was the home of the emperors: the centre of Beijing and, metaphorically, the universe. Here, open spaces were prevalent, in the gardens and courtyards of temples and palaces. As one moved outwards into the Imperial City, which housed high ranking imperial officers, the Inner City, occupied by bannermen and other officials, and finally the Outer city, the availability of open space gradually decreased.4 Open space thus was a marker of status and inextricably linked to the imperial house. The foundation of the Wanshengyuan and the creation of a public space on formerly imperial and temple grounds, was radical. Much like the Singapore zoo, it attracted non-elite members of society to marvel at its animals.5 However, in Beijing this held extra weight, due to the pre-existing norms and connotations of open space. Though most visitors were of the middle class, it was still a significant reshuffling of the status quo.6

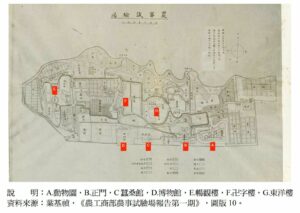

Figure 2: The Experimental Agricultural Complex7

As Mingzheng Shi suggests, the Wanshangyuen was a spatial representation of the growth of the public sphere in early republican China.8 Prior to the nineteenth century menageries had been the sole purview of rulers and the wealthy. They were private celebrations of the control exercised by the privileged over the natural world. Animals in Beijing’s menageries were often used in imperial rituals such as the Royal Ploughing Ceremony or the Spring and and Autumn Royal Hunting Ceremonies.9 A zoological park open to the public, however, had different connotations. It was a message that a government could provide for its citizens, an image the early republican Chinese government wished to pursue.10 Much like the zoo in Batavia and Singapore, the Wanshengyuen was attached to a Botanical Garden and various research facilities. In Figure 2 we can see the complex in which the Wanshengyuen (A) was housed, as well as various experimental agriculture beds, a museum (D), and sericulture hall (C). However, unlike the colonial institutions, the Wanshengyuen inherently appealed to the common citizen given its novel place in Beijing’s spatial culture. Thus, the Wanshengyuen could be connected to a wider project of research intended to improve the lives of all citizens, unlike the zoos in Batavia and Singapore which were seen more as colonial tools.

The Wanshengyuan is an interesting case study into the ways parks could be used by governments in different Asian contexts. While the zoological gardens of Singapore were certainly seen by the public as a symbol of modernity, as they bemoaned the absence of such a symbol in their city once it had been closed, that was never its purpose for the colonial government.11 Rather it was an extension of the botanical gardens projection of colonial control and power, self-aggrandizing rather than communally uplifting. The Wanshengyuen, on the other hand, was used by the early republican government to show that they were abandoning the exclusionist policies of the past and emphasising public welfare.10 As such, though the Wanshengyuen was perhaps spatially similar to previous zoological parks in Asia, it was in fact a culturally distinct entity.

- Mingzheng Shi, “From Imperial Gardens to Public Parks: The Transformation of Urban Space in Early Twentieth-Century Beijing”, Modern China 24:3 (1998), p. 229. [↩]

- Timothy Barnard, Nature’s Colony (Singapore, 2016), p. 85. [↩]

- Peking – Contagion – CURIOSity Digital Collections (harvard.edu) [↩]

- Mingzheng Shi, “From Imperial Gardens to Public Parks: The Transformation of Urban Space in Early Twentieth-Century Beijing”, Modern China 24:3 (1998), p. 220. [↩]

- Timothy Barnard, Nature’s Colony (Singapore, 2016), p. 96. [↩]

- Mingzheng Shi, “From Imperial Gardens to Public Parks: The Transformation of Urban Space in Early Twentieth-Century Beijing”, Modern China 24:3 (1998), p. 250. [↩]

- Xin Shixue, “From Imperial Menageries to Public Zoological Garden: Captive Wild Animals at the Qing Court”, New History 29:1 (2018), p. 24. [↩]

- Mingzheng Shi, “From Imperial Gardens to Public Parks: The Transformation of Urban Space in Early Twentieth-Century Beijing”, Modern China 24:3 (1998). [↩]

- Xin Shixue, “From Imperial Menageries to Public Zoological Garden: Captive Wild Animals at the Qing Court”, New History 29:1 (2018). [↩]

- Mingzheng Shi, “From Imperial Gardens to Public Parks: The Transformation of Urban Space in Early Twentieth-Century Beijing”, Modern China 24:3 (1998), p. 233. [↩] [↩]

- Timothy Barnard, Nature’s Colony (Singapore, 2016), p. 111. [↩]

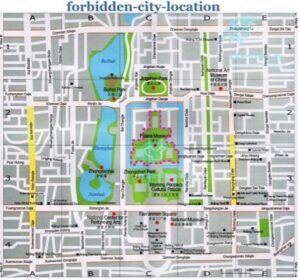

Figure 1. Map of Jingshan Park and the Forbidden city

Figure 1. Map of Jingshan Park and the Forbidden city

Figure 3. The restored Buddha statue in Wanchun Pavilion

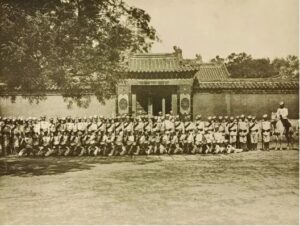

Figure 3. The restored Buddha statue in Wanchun Pavilion Figure 4. Russian Occupation of Jingshan Park, 1900

Figure 4. Russian Occupation of Jingshan Park, 1900

Excerpt 1. the exclusivity of passengers

Excerpt 1. the exclusivity of passengers Excerpt 2. The instruction of the dress code

Excerpt 2. The instruction of the dress code