The Western exhibition of the Cairene, according to Mitchell, was defined by an “objectness of the Orient, as a picture-reality containing no sign of the increasingly pervasive European presence required that the presence itself.”1 While a key plank to Mitchell’s heuristic for explaining the particularity of the Western “exhibition” was the reflexive nature of Arabic sources, I ask if an exhibition’s location matters at all. By comparing the 1922 Malaya Borneo Exhibition in Singapore and the 1924 British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, I argue the importance of colonial power relations that undergirded both exhibitions about “British Malaya”. Indeed, both led to ironic results: the former in terms of Singapore’s spatial realities and the latter in terms of the attempt to artificially engender the “kampung.” I conclude by demonstrating the lasting consequences of spatial representation in post-colonial societies.

The 1922 Exhibition was the brainchild of colonial administrators’ attempt to stimulate local trade. Held in Singapore from 31 March to 17 April 1922, it did so by portraying a singular, Malayan unity, especially under the eyes of the visiting Prince of Wales.2 Unlike previous exhibitions where Malay states were represented individually,3 the plurality of groups on display necessitated coordination with a gamut of organisers for the sprawl of “Sulu and Dyak dances, mak yong and menora dance forms from Kelantan, boria theatre from Penang, mek mulung theatre and wayang kulit shadow play from Kedah, regimental band music and even a Tamil fire dance.”2 Furthermore, the fair contained a “small model village” full of “real” Dayak and Murat representations “dressed in leopard-skin and full headdress.” Ironically, while undermining a “single Malaya”, the Exhibition was a success for private commerce built on the essentialisation of the “reality” of tribes from the Malay Archipelago. That the sight surprised visitors (urban Singaporeans) offered the most ironic demonstration of the simultaneous premises of “authenticity” and “distinctiveness” of the Dayak vis-a-vis urban Singaporean. Yet, under a colonial structure, they were hierarchically the same under the imperial gaze toward “Malaya Borneo.”

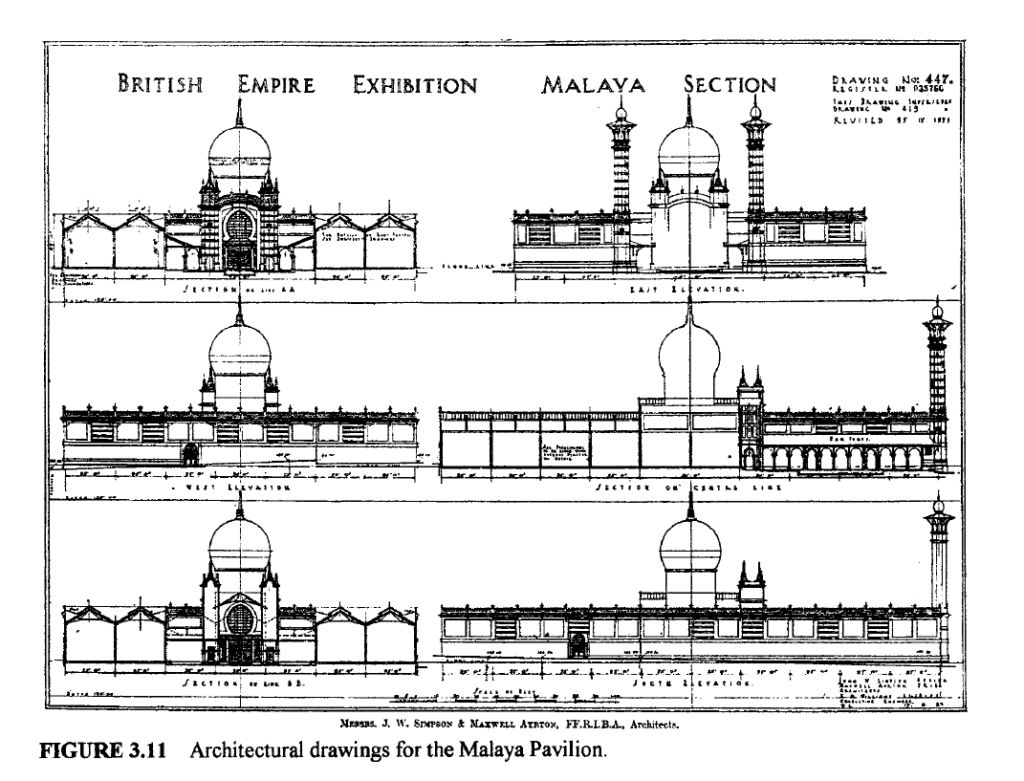

Two years later, the British Empire Exhibition in 1924-5 at Wembley articulated this vision more clearly by parading British Malaya (comprising Malaya Borneo, but decidedly not named as such) along other “trophies of empire.”4 Curiously, this naming discrepancy was rendered even more ironic since the British Rajah of Sarawak declined a collective showing under the Malayan banner to the chagrin of Andrew Caldecott.5 Of course, the actuality of “British Malaya” was a collection of Brunei, the Federated Malay States, the Unfederated Malay States and the Straits Settlements – each of which constituted a plethora of political and ethnic entities. Almost as a refraction of the metropole’s view of Malaya, The Times’ supplement on 23 April 1924 celebrated its “wonderful natural resources of a rich tropical country,” as spatialised by “adapted Musulman architecture.” The Times’ details of the Malayan Pavilion at Wembley were reproduced in Singapore via The Straits Times, emphasising to its readers the recreation of Malaya’s “tropical locale.”6 For the British visitor, “twenty Malayan artisans and attendants” that comprised “weavers, silversmiths, geological assistants… and carpenter to attend to the different sections” were housed in a “fenced kampong” at the rear of the building. The Pavilion eminently contained characteristics of the textbook “Exhibition” insofar as onlookers consumed “picture-as-reality,” unaware of its artificiality. Finally, it was morbidly replete with the irony of an alleged death of Halimah bte Abdullah due to the “kampung” conditions she was subject to.7

Both exhibitions, characterised by different ironies, yielded appalling evidence of Malaya’s imperial worth: its tin and its islands. Yet, both exhibitions were spatialised in radically different ways. In 1924, British visitors at Wembley went away with an identification of British Malaya in terms of “Moorish-Arabesque” (Figure 1) architecture. Yet, one surviving picture of the 1922 Singapore exhibition (Figure 2) shows no such instance of such architecture in precisely a constituent location of British Malaya, rendering the irony of exhibition as “reality” even more jarring. The second irony for this is the historical transmission of Indo-Islamic architecture. Indo-Islamic, or Indo-Saracenic, was a style brought out of British India and across empire by British architects after they had worked in or visited India.8

Figure 1 – the Indo-Islamic Style, associated with Malaysia, was brought out of British India by colonial architects

Figure 2 – https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-17/issue-3/oct-dec-2021/prewarphotography/

The historical, spatial irony of the Indo-Islamic remain spatially poignant today. On one level, tourist-facing resources slap this designation of “modern Arab” or “Moorish” architecture onto Masjid Sultan in Singapore. While the Mosque was originally built by Sultan Hussein Shah himself in 1823 like early mosques in the Malay Archipelago, the colonial architect Denis Santry in 1924 spearheaded an Indo-Islamic rejuvenation of the Mosque, in spite of the “presence of Arab, Indian, Tamil, Bugis, local Malay and Javanese representatives in the mosque committee.”9 Beyond the visitor’s gaze, the Mosque’s iconic architecture10 today has been cast as a foremost symbol of ethnic and racial pluralism in Singapore by the state and by Singaporeans. Near the Mosque is the Sultan’s previous residence, which had been acquired by the government in 1999 for the construction of the Malay Heritage Centre.11 Finally, this symbolism has been refracted outward into foreign relations. The street on which the mosque is situated – Muscat Street – hosts 8 metre-high granite arches displaying ornate Omani carvings, murals that were painted by Omani artists and tiles that were specially selected and imported from Oman.12 Plaques underneath the arches memorialise, in Arabic and English, the street’s redevelopment as a collaborative project between Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority and Oman’s Muscat Municipality in 2012.

Having first demonstrated the ease with which one can problematise two colonial representations of reality, this post has then focused on the far-reaching implications of spatial representation. As the history of Indo-Islamic architecture indicates, what is far more deserving of academic attention is the ease with which memory and spatial representations travel. Embedded within these transmissions is the often ironic role of colonialist and imperialist power structures.

- Timothy Mitchell, “The World as Exhibition”. Comparative Studies in Society and History 31, no. 2 (1989): p. 228. [↩]

- https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-17/issue-3/oct-dec-2021/prewarphotography/ [↩] [↩]

- Jesse O’Neill. ‘Reorienting Identities at the Imperial Fairground: British Malaya and North Borneo’, Design History Society Conference 2019: The Cost of Design, 5–7 September 2019, Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK. [↩]

- Chee Kien Lai, “Concrete/Concentric Nationalism: The Architecture of Independence in Malaysia, 1945-1969” (PhD Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 2005), pp. 124, 129-145 [↩]

- Assisting Secretary to the Federation government, and chief of the Malayan and Bornean exhibits. O’Neill, ‘Reorienting Identities at the Imperial Fairground’, p. 5 [↩]

- Lai, pp. 143-45. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Lai, p. 109. [↩]

- Lai, p. 110. [↩]

- https://www.sg101.gov.sg/resources/connexionsg/sultanmosque/ [↩]

- https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/politics/budget-debate-istana-to-be-restored-malay-heritage-centre-redeveloped [↩]

- See: https://www.mfa.gov.sg/Newsroom/Announcements-and-Highlights/2017/12/Muscat-Street [↩]