In his chapter “Important Attractions” Andrew Field relied mostly on the mosquito newspaper 晶報 Jing Bao (Crystal) to discuss the evolution of the ‘dance hostess’ as a vocation. In the social imagination of 1930s Shanghai, a dance hostess – previously looked down upon by a café waitress in courtesan-era Shanghai – was now a position that a film star aspired to. One inherent limitation of this source reliance is Field’s tacit, diligent acknowledgement that he could not overextend his argument when claiming dance hostesses’ self-identification in newspapers.1 Furthermore, Field was unable to confidently historicise the way gang activity ‘infiltrated’ dancehalls as spaces.2 Inspired nonetheless by this discussion, I explore in this post a parallel moral panic in the 1950s Chinese-language mosquito press within Singapore about the 歌台 getai (literally singing stage, but in effect a dancehall). Where Shanghai discourse examined the dancehall’s main figure of attraction – the hostess – in Singapore the mosquito press’ moral panic descended upon the peripheral figure (in performance terms) of the striptease performer. While both moral discourses had the same function of dislocating the controversial performer from their space, the parameters of each controversy was governed by specific expressions of nationalism.

Unlike contemporary imaginings, the getai in 1950s Singapore was a remnant of the Japanese Occupation when the Japanese administration used the Beauty World, Gay World, and Happy World amusement parks to host cinemas, stalls and gambling farms for fiscal revenue.3 While there were similar styles of variety shows that had originated from Shanghai in the 1930s, the three “Worlds” were the locus for getai activity in post-war Singapore.4 In an industry with low barriers to entry and exit, poaching of talent was common, and a getai was driven by a desire for immediate revenue. Thus, when taken in isolation, the striptease was but one of a repertoire of acts in this profit-driven enterprise.

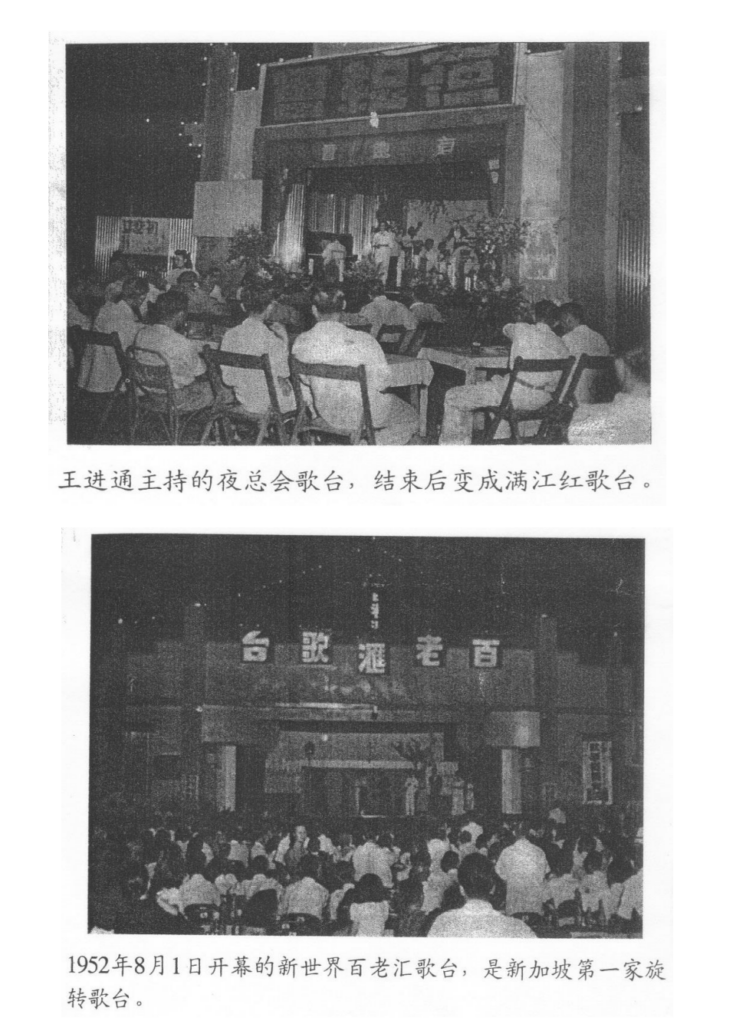

Photographs of getai from Wang’s 新加坡歌台史话 in Ho’s M.A. Thesis

However, the peripheral getai striptease performer was invariably brought to the front within the distinct discursive spaces that were the English- and Chinese-language presses. In showing this, I first highlight the need to lend weight to 1950s Chinese-language ‘mosquito newspapers’ because of their broad-based popularity.5 Secondly, the Chinese-language press notably had direct traces of cultural discourse from the 1930s Shanghai press. One adaptation6 of the Chinese intellectual 劉吶鷗 (Liu Na Ou)’s words was his charge that art should be pursued to entertain the masses and present the “sensual pleasures of the urban city.”7 Where Liu was writing of 1930s soft-core films in Shanghai, a 1953 Saturday Review article appropriated Liu to lyricise the effect of watching a striptease: 心灵坐沙发椅 and 眼睛吃冰淇淋.8

The spotlight on striptease overshadowed the wider post-colonial moral panic in the 1950s surrounding “yellow” culture. Both English and Chinese language discourse excoriated moral depravity, known as “yellow” culture, within the epoch’s Overton window of “anti-colonial sentiments, burgeoning Malayan consciousness, anxieties over rapid urbanisation, and fears of rampant moral debauchery.”9 Yet, as Ho has shown, the 1950s discourse was destabilised precisely because the Chinese-language press (mosquito or otherwise) had no “homogeneously puritanical or left-inclined” moral position.10 Mosquito newspapers were often hypocritical and more concerned with performative condemnations of rival newspapers that endorsed striptease, slapping rivals with labels such as “yellow, influential publication”.11 On the other hand, mainstream Chinese intellectuals were divided, portraying strippers anywhere between 色情販子 (vendors of sex) and purveyors of art.12 Finally, strippers themselves were far less inclined to wax lyrical over the artistic value of their own profession.

Thus, the 1950s moral panic surrounding striptease in Singapore was largely framed by the specificity of social anxieties surrounding nationalism and urbanisation. When put in conversation with the 1930s Shanghai discourse, it becomes clear that these intellectually tenuous moral panics simultaneously engendered and were caused by despatialisations of popular entertainment. Regardless of their performative gravity, both the Shanghai dance hostess and the getai stripper were dislocated from their social spaces and their underlying power structures, only to be reconstructed within the vacuum of printed columns as lightning rods for moral significance.

- Andrew Field, Shanghai’s Dancing World: Cabaret Culture and Urban Politics, 1919–1954 (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2010), pp. 137-140. [↩]

- Ibid., pp. 134-136 [↩]

- CM Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore, 1819-2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), p. 207. [↩]

- Zhen Chun, Wang, 新加坡歌台史话 (Singapore: 新加坡青年书局, 2006), pp. 67-70. [↩]

- This is especially relevant in the historiography of nationalism in Singapore because it rarely engages with the Chinese masses beyond the activities of student activists or intellectuals. Hui Lin, Ho, “The 1950s Striptease Debate in Singapore: Getai and the Politics of Culture” (M.A. Thesis, National University of Singapore), p. 11 [↩]

- Saturday Review, Nov 21, 1953, pp. 15-17. [↩]

- Leo Ou-fan Lee, Shanghai Modern: The Flowering of a New Urban Culture in China, 1930-1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 92. [↩]

- Taken literally, Liu writes that the soul was “resting on the sofa” and the eyes were “eating ice-cream”; Ho translates this as “repose for the soul” and “feast for the eyes.” Ho, “The 1950s Striptease Debate in Singapore”, p. 51. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 54. [↩]

- Ibid., p. 58. [↩]

- 夜燈包 Ye Deng Bao, Mar 19, 1953, p. 2. [↩]

- 生活報 Sheng Huo Bao, May 8, 1956, p. 7. [↩]