The early twentieth century saw rising literacy and expanding commercial popular presses in China and Japan. As such , the interwar period ushered in a boom in women’s magazines. These publications targeted female issues and became guides for household management and taste. However, the approaches to domestic control espoused by Chinese and Japanese counterparts differed. By comparing the contents of Shufu no Tomo and Ling Long, we can see the diversity of domestic revolutions occurring in China and Japan in the interwar period.

Shufu no Tomo, commonly translated as Housewife’s Companion, was first published in 1917, and by 1925 was the most popular Japanese women’s magazine, selling over a million copies a month.1 Its pages contained articles concerning budgeting, housekeeping, fashion, and dance. Ling Long, meaning elegant and fine, was published in Shanghai between 1931 and 1937. It contained tips on how to raise children, outlined typical household duties, and covered Hollywood films and pop-culture.2 At about five by four inches in dimension, it became popular as an accessory just as much as a publication. Zhang Ailing claims, “every female student had an issue of Ling long magazine in hand during the 1930s”.3

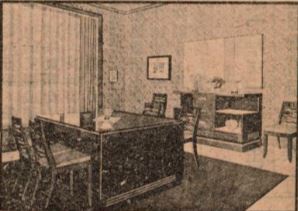

A notable difference between the two are the types of advertisement featured in each. Sand notes that the items advertised in Shufu no Tomo were overwhelmingly small, personal items such as medicines and cosmetic products. There were rare instances of kitchen appliances being advertised. However, there is a complete lack of furniture.4 Instead, there was a focus on what Japanese women could make themselves to spruce up the home. For instance, the edition published in June 1926 encouraged women to sew their own curtains to adorn cabinets and windows during the summer time.5 In contrast, Ling Long contained advertisements for furniture in almost every edition.

Advertisement for dining room furniture, Ling Long Issue 1

Advertisement for a chair, Ling Long Issue 40

Advertisements such as these promised the transformation of the home into a site of happiness through purchase of furniture. They were positioned as objects of desire, and purchasing them ensured entrance and acceptance into the leisure class.6 Apparent is the discrepancy in the intended audience of the two magazines. The readers of Shufu no Tomo evidently were presumed to have less purchasing power than their Shanghai counterparts. While Ling Long encouraged the creation of a comfortable middle class through consumerism, Shufu no Tomo emphasised thrift available to all classes of society. Perhaps this is systematic of Ling Long’s more elite urban readership, but it also shows the differing approaches to creation of domestic spaces. The fact that the latter half of all early Ling Long editions was dedicated to the consumption of Hollywood culture emphasises how Shanghai women were more deeply entrenched in global economic networks, which spilled over into the methods by which they shaped their homes.

Instead of promoting the control of domestic space through the exercise of economic power, Shufu no Tomo encouraged a more hands on involvement throughout the process of making homes. In a volume about middle class housing published by the women’s magazine, readers are warned to hire young architects instead of old carpenters as they will be more sympathetic towards desires for western style housing. Whereas the old carpenter would associate such style with schools, post offices, and other public buildings, the architect will be more open minded about implementing western building practices in the home.7 Indeed, one author in the November 1921 edition of Shufu no Tomo stated, “we have left the era of living for the house and must now progress into the era of building houses for living”.8 From this and other articles critiquing and promotion of certain architectural trends, we can see that readers of Shufu no Tomo were envisioned as having a significant role in the design and construction of homes. Japanese interwar women could partake in this traditionally masculine sphere in order to have greater input on the fundamental formation of their domestic spaces.

In addition, Shufu no Tomo encouraged readers to take up newly rationalised domestic practices. While the kitchen is a notably absent space in Ling Long, as cooking was seen to be the responsibility of servants,9 the kitchen took on new significance for Japanese women in the interwar period as domestic work came to be seen through a scientific lens.10 Household work came to be seen as an important part of promoting a family’s wellbeing and efficiency,. Taught in new Japanese Women’s Higher Schools, knowledge was then further disseminated by publications such as Shufu no Tomo. The kitchen thus became a site for Japanese women to utilise their knowledge of nutrition and hygiene to support their families, and exercise domestic power.

The types of domestic control espoused in Shufu no Tomo and Ling Long are thus divergent. While Shufu no Tomo promotes the domestic shaping through the practice of daily chores, handcrafted decoration, and architectural input, Ling Long promotes the consumption of prebuilt domestic styles, with agency being found in choices of consumption. By buying sets of furniture and emulating homes seen in Ling Long, Shanghai women were participating in a more global creation of middle class domesticity, borrowing from and performing for western audiences. These conflicting representations of domestic control presented in Ling Long and Shufu no Tomo illuminate the different ways in which interwar Asian women were able to exercise agency within the domestic spaces.

- Jordan Sand, House and Home in Modern Japan (Cambridge, 2003), p. 163. [↩]

- Louise Edwards, “The Shanghai Modern Woman’s American Dreams”, Pacific Historical Review 81:4 (2012), p. 574. [↩]

- Elizabeth La Couture, Dwelling in the World (New York, 2021), p. 194. [↩]

- Jordan Sand, House and Home in Modern Japan (Cambridge, 2003), p. 346. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 347. [↩]

- Elizabeth La Couture, Dwelling in the World (New York, 2021), p. 203. [↩]

- Jordan Sand, House and Home in Modern Japan (Cambridge, 2003), p. 275. [↩]

- Ibid, p. 317. [↩]

- Elizabeth La Couture, Dwelling in the World (New York, 2021), p. 211. [↩]

- Jordan Sand, House and Home in Modern Japan (Cambridge, 2003), p. 94. [↩]