,The Yu Lan Jie (盂蘭節), or the Hungry Ghost festival provides an interesting lens to view the soujourner communities and native place associations in major Asian cities through. This can be seen in the symbolic respect of the soujourner ghost, or the community building aspect of these festivities but also the contested space itself where these festivals and rituals take place – where foreign influence and urbanisation threatened the communities’ access and claims to the land and the Yu Lan Jie celebrations.

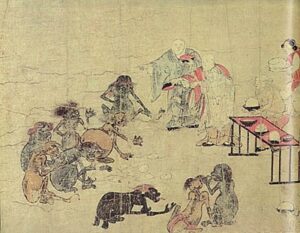

Playing a role in Taoism, Chinese folk religion, and Chinese Buddhism, this important festival has muiltiple reported origins, but can be traced back to an ancient Indian buddhist scripture known as Yulanpen Sutra, from which the name of the festival derives. The Sutra relays the story of Maudgalyayana, who goes on a journey to visit his deceased parents, only to find his mother in the realm of Preta, the hungry ghost. After his mother refuses his rice, Maudgalyayana is informed by Buddha that the only way he can feed and save her is by providing offerings at his monastic community during Pravarana, roughly corresponding to the 15th day of the 7th month (1). Drawing on this, the Chinese celebration falls on the 7th lunar month, considered the ghost month, where on the 15th day of that month the gates to hell and heaven open and the ghosts are believed to pass into the human realm. Rituals and offerings are given to satisfy these ghosts in both burial grounds and the house, with the intended purpose of ensuring prosperity and ward off bad luck. I bring up the origins of this festival to trace what the early depictions of this festival seem to align with, the family. In these images, celebrations seem to be more intimate and more household based rather than celebrated by guilds or communities.

This more personal setting however, applies only to one side of the festival: household celebrations were specific to ancestral ghosts, however, separate celebrations existed in the heart of the community – often in regional temples and burial grounds or marketplaces – for the ghosts with no descendants or who have been forgotten (2). Indeed, the potent image of the ‘hungry ghost’, almost animalistic in their distress, seem to align more with these forgotten, emotionally charged ghosts than the ancestral spirits. Therefore, when cities like Shanghai starting rapidly urbanising in the 19th century, the native place associations which sprang up found this festival an important event to show their regional solidarity. The ‘sojourning ghost’, as Goodman aptly puts it, and its plight as a foreign entity in the living realm, struck a cord with the lonely sojourners in the city without families (3). Indeed, a stone inscription on a Ningbo artisan association building in Shanghai seems to make this exact parallel when it says: “Living, we are guests from other parts; dead, we are ghosts from foreign territory.” (4)

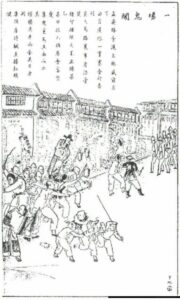

The communal festivities include rituals performed by Taoist priests or Buddhist monks, – who were sometimes transported from their native regions- bonfires burning spirit money and clothes to transfer to the pauper ghosts, stage performances, costumed processions and a large collective banquet for members of the native place associations (5). These activities led to a large amount of flexibility in cultural expression, lavishness and scale, allowing a fluid framework for members to exert their regional identities through far from home. It allowed expression from across the social strata of the native place association, not just the Huiguan leaders (6). For the more )wealthy and prominent regional communities, like Guangdong and Ningbo, these processions and religious ceremonies were the perfect opportunity to exert their legitimacy and prestige as a collective. The festivities also prompted social welfare provisions amongst the association, with cakes made for the celebration being distributed to the poorest in the group (7). welfare did act as a point of critique of these celebrations, particularly when funds for disaster and conflict relief were being sought from those affected in their transnational communities. As a one writers chides “The yulanpenhui is to relieve the homeless ghosts. But they are already dead. . . . Why not help the living?” (8). With the hungry ghost celebrations and public charity both important for the construction of status for the Huiguan elites and the community’s identity such a critique almost challenges an ordered hierarchy of the prestige making activities of native place associations. While public charity and mutual aid objectively seems the more worthy cause for the whole regional group, somewhat ironically it exists as the less accessible option for the lower strata to participate in than Yu Lan Jie which remained popular well into the 20th century.

The final thought I wanted to discuss about the significance of the festival was what it reflected about the ongoing struggle soujourner communities faced in regards to the burial grounds and guild halls where they would perform some of these rituals, and the very real dead they were temporarily storing before transporting them to their native regions. Rapid urbanisation of cities didn’t just lead to the rise of migrant soujourner communities in cities, but also led to the problem of relocating graveyards upon the desire to expand the boundaries of the city. In Shanghai, this problem was often characterised as a conflict between the Chinese communities and the Western powers. This could be seen generally through the western discourse of public health and plague prevention, objecting to the sojourner guilds coffin repositories in the urban areas (9). More specifically though, it is possibly most famously seen through the two conflicts between French authorities and the Ningbo people regarding the location of Siming Gongsuo and coffin repository in 1874 and 1898. While an article in the agreement between China and the international settlement specifically forbade the western powers from removing the dead from their lands without explicit permission, because said article also stated that the no new Chinese coffins should be placed within their limits, many public cemeteries quickly decided it was in their interest to agree and relocate (10). Guild graveyards proved to be more stubborn, particularly the Siming Gongsuo. Given all the discussion above, it can be understood why these locations would be more precious to the soujourner community, away from their home and family. The rise in popularity of the commercial urban graveyards in Shanghai are possibly evidence that people were feeling the distance between the city and the newly relocated, isolated graveyards. While the Ningbo riots can be characterised as examples of early popular nationalism, it’s important to contextualise these events in the broader trend of urban displacement. Thomas S. Mullaney interactive digital volume The Chinese Deathscape Grave Reform in Modern China virtually maps this phenomenon and notes that this is just as much a contemporary issue as it is historic (11). While the festivals may have spiritually marked the migration of the dead in the living realm, burial re-locations make the dead physically migrants in, what Mullaney terms, the landscape of death. This not only makes the metaphor between sojourner and ghost complete, but also indicates why such a festival has been historically so important to migrant communities, as it is not only culturally enriching but such cultural enrichment is under a continuous mounted threat from urbanisation.

(1) Jean DeBernardi,. “The hungry ghosts festival: a convergence of religion and politics in the chinese community of Penang, Malaysia.” Asian Journal of Social Science 12, no. 2 (1984), pp.25-34, p.26

(2) Debarnardi, “The hungry ghosts”, pp.27-29

(3) Bryna Goodman, Native, Place, City, and Nation: regional networks and identities in Shanghai, 1853-1937, (University of California Press, 2023.), p.96

(4) Cited in Goodman, Native, Place, City, p.96

(5) Debarnardi, ‘The hungry ghosts’, p.27-29,

(6) Goodman, Native, Place, City, p.100

(7) Debarnardi, ‘The hungry ghosts’, p.28

(8) Goodman, Native, Place, City, p.99

(9) Ibid.p.163

(10) Christian Henriot, ‘When the Dead Go Marching in’, in Mullaney, Thomas Shawn, Christian Henriot, Jeffrey Snyder-Reinke, David William McClure, and Glen Worthey. The Chinese deathscape: Grave reform in modern china. Stanford University Press, 2019.

(11) Henriot, ‘When the Dead’.