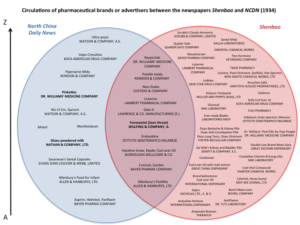

One of the most eye-catching aspects of newspapers, no matter what era, are advertisements. Ever since the advent of mass production and commercial sales, enterprising businessmen have attempted to sell a whole panoply of products. Chinese newspapers seem to have a penchant for advertising pharmaceutical products. A curious collection of diagrams published in 2017 highlights the overlaps between ads in the Shenbao and North China Daily News (NCDN) triggered an interesting deep dive into the appearance of specific ads in Chinese newspaper sources of the early 1900s. [1] These diagrams highlight an interesting evolution in the types of advertisements that appeared in Chinese Newspapers as perspectives on health evolved. Newspaper advertisements are powerful indicators of the zeitgeist of a region. In the case of pharmaceutical advertisements, it represented a powerful shift in the discourses surrounding hygiene and health in China. This was especially true in treaty ports, where increased accessibility to commodified drugs changed the nature of what health or weisheng (衛生) meant.

We begin with the primary source accounts found in newspapers from the early 1910s to the late 1940s, which denoted a marked shift in the number of pharmaceutical advertisements found in China-based newspapers. Shenbao in particular seems to have an eclectic mixture of pharmaceutical companies from Japan, the UK, the US and Germany. From 1914 to 1949, Bayer was commonly featured in both Shenbao and NCDN selling Aspirin and Cresival. While Aspirin is a household name in today’s day and age, used for the treatment of headaches and as a blood thinner. In the specific case of the Jiangsheng Bao (literally the sound of River Newspaper) a newspaper produced in Xiamen from 1918 to 1951, these pharmaceutical advertisements are so ubiquitous that most daily papers had at least one mention of medication. Once again, we see Bayer with a fairly large ad for Eldoform (anti-diarrheal) Mitigal (an ointment used to treat scabies) and Cresival. Of the many drugs advertised, Cresival seems to be the most mysterious. In the Jiangsheng Bao’s account of this medicine, it claims to clear phlegm and be the foremost cure for cough. In essence, a very good cough syrup. Bayer’s significant investment in Chinese newspaper advertisements seems quite unusual when taken out of context. Why would a German pharmaceutical company be interested in selling minor medications to people halfway across the globe?

Bayer Advertisement in 06/09/1932 Issue of Jiangsheng Bao [2]

The increased mentions of this medicine and for that matter, all types of medication indicated a significant shift in how Chinese people saw health as acquirable and consumable. In Ruth Rogaski’s Hygenic Modernity, she highlights how introduction to western culture increased the accessibility of ready-made remedies. [3] She discusses the wider adoption of Western hygienic norms throughout the 1920s and 30s in Treaty Ports throughout China: “For one and a half yuan, one could obtain weisheng in a pill.” Rogaski focuses most on the aggressive advertising of “Dr William’s Pink Pills for Pale People” a drug that was advertised heavily in the Shebao and NCDN from 1914 to 1949. [4] This pill was sold as a miracle cure for everything from “insomnia to intestinal worms”. She cogently comments on how these newspaper advertisements adapted themselves to the Chinese context, targeting a variety of figures such as the traditional male head of the household and their wifely counterparts. The ailments that these pills targeted were relevant to the discourses surrounding modernity and medicine at the time. [5]

The marked shift in how hygiene was seen as easily consumable and a mark of modernity drove pharmaceutical companies to set up shop in treaty ports such as Shanghai. Bayer set up its first Chinese factory producing Aspirin in 1936. [6] It seems that alongside the aggressive advertising in newspapers, Bayer was capitalising on this weisheng revolution and finding a market for commodified health. Their increased presence in newspaper advertisements across China was quite intentional. As the social discourse surrounding hygiene and modernity in China grew, so did the consumption of these “health consumables” that could improve not just the general health of the average Chinese person, but the health of the overall state and civilisation. These pharmaceutical newspaper advertisements in the Shenbao, North China Daily News and Jiangsheng Bao reflected on the rapidly evolving ideas on health and modernity in China that pervaded that period.

[1] ‘Circulations of pharmaceutical brands between the newspapers Shenbao and North China Daily News (1914-1949)’, MADSPACE, 5 May 2017, <https://madspace.org/cooked/Drawings?ID=128> [accessed 5 February 2022].

[2] ‘Jiangsheng Bao’, Archive.org, 06/09/1932, <https://archive.org/details/jiangshengbao-1932.09.06/page/n6/mode/2up> [accessed 5 February 2022].

[3] Ruth Rogaski, Hygenic Modernity: Meanings of Health and Disease in Treaty-Port China (London, 2004), p. 227.

[4] Ibid, p. 229..

[5] Ibid, p. 230.

[6] Bayer, ‘Bayer China History’ <https://www.bayer.com.cn/index.php/AboutBayer/BayerChina/2nd/History?l=en-us> [accessed 5 February 2022].