To borrow from Edward Said, whose writings occupy an almost exhaustive historiography on his own, “contrapuntal reading” in literature invites the reader to ponder writing actively says and does not say about one’s disposition and blind spots. Insofar as scholars agree that tourism both reflected and reinforced efforts to build and maintain overseas empires,1 officially-affiliated travel guidebooks are clear opportunities for discursive analysis of the “self” and “other.” The historiography of Japanese colonialism in Korea is no different.2 The concerted Japanese attempt to market the Korean peninsula for foreign revenue, I argue, is best evinced by Terry’s Japanese Empire.3 However, by examining the presentation of Korea within a Western-facing guidebook of Imperial Japan, I argue that the tenuousness of “Othering” in an “Occidental”-facing book evinces Hom’s clarification of imperialism as “textured by uneven gradations of sovereignty and sliding scales of differentiation that bind colonial past and imperial presence.”4

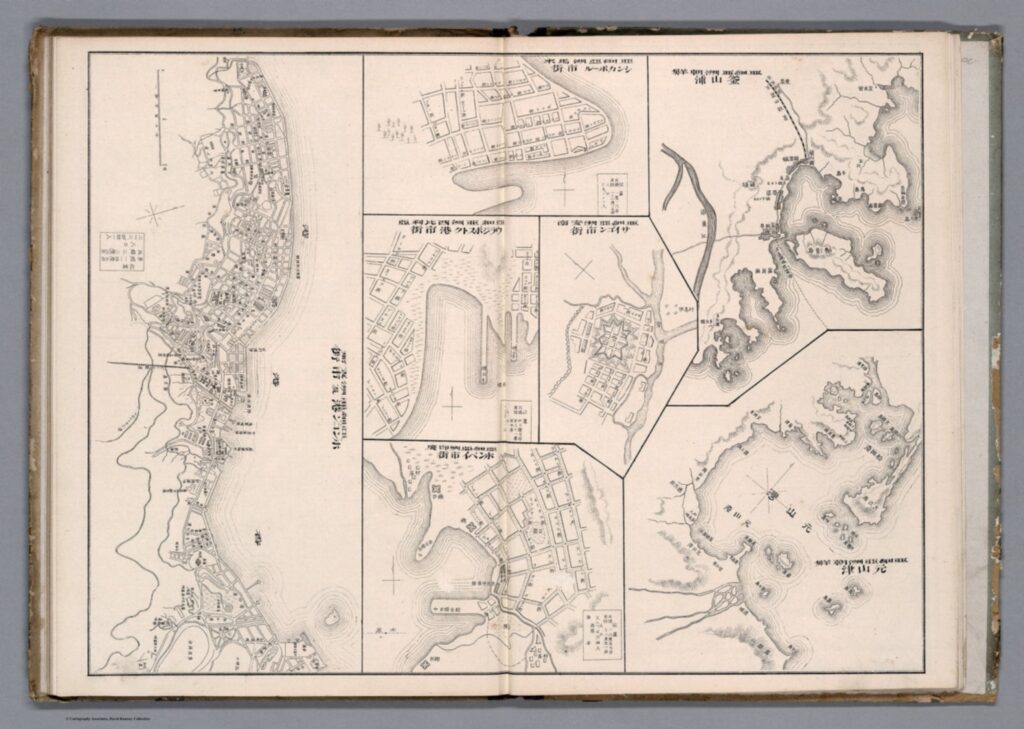

Firstly, Terry argues that Japan is as geographically and culturally specific as it is “typical” for an Oriental entity. This discourse is presented both in terms of climate and geography. On page lxi (of a 283-page long preliminary information section) Terry argues that it is ‘quite those of our dreams’ to see Japan and ‘learn its charm is equivalent to drinking the waters of Guadalupe.’ Contemporaneously, the Korean landscape is both littered with ‘limp and enervated Europeans from the torrid south’ while devoid of a ‘good gov’t to make it one of the most opulent countries of the gorgeous East.’ (698-99) In terms of culture, the text assumes fixed profiles of the tourist and those viewed by tourists. For Terry, there is a single, tourist profile of a traveller who has embarked on a long journey from Western Europe, Australia, or America, and the essentialism of the other even does not spare countries from the Mediterranean. Conversely, the object of the rigidly defined “Korean” man is impenetrable and physiognomically fixed. “[Like] the Chinaman, he has, in his fathomless conceit and besotted ignorance, a sturdy and unshakable faith in his own impeccability,” among other pejorative judgements. (719) This essentialist discourse appears indistinguishable from the liberal comparisons drawn to men from Spain and specifically South Italy insofar as poor cultural traits are concerned. In contrast, the Japanese man is “non-controversial and dignified” and Japan is made of ten different “native races [that] dwell within the Japanese Empire.” (clv-clvi)

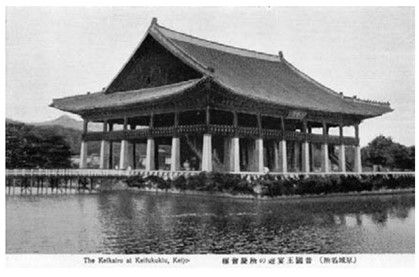

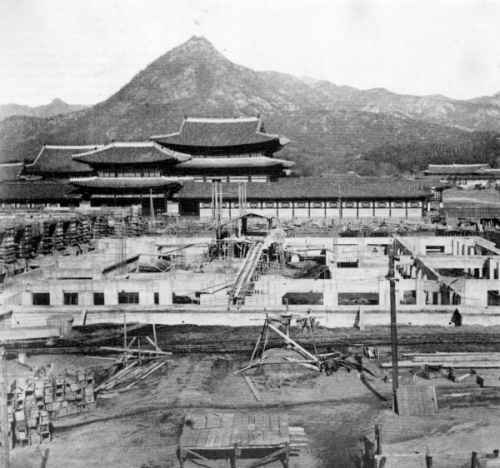

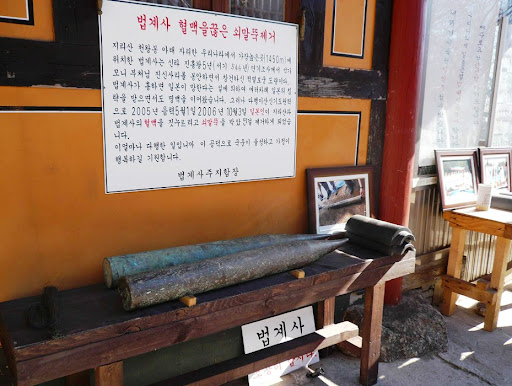

Yet, what Terry says about Korean history becomes problematised beyond the level of the “Occidental” perspective. On one hand, the hierarchy of civilisations is clear when Terry presents an entity characterised by corruption and ineptitude. Terry particularly describes the Three Kingdoms period as replete with each kingdom having (apparently) ‘episodes of national triumph and reverse,’ (bold is mine) and that the source of civilisation in Korea eventually derived from Japan. Yet, even this hierarchy was ‘only replaced in the latter half of the 19th cent. By the higher civilisation of Europe.’ (709) Finally, the Japanese ‘introduction of civilisation and enlightenment’ is a tangible process that can be tracked if one requests the Government General of Chosen’s ‘Annual Report on Reforms and Progress in Korea’.

On another level, Terry’s unabashed, liberal reference to Joseph H. Longford’s The Story of Korea reflects the ways in which imperial tourism refracts Japanese imperial knowledge about Korea. According to a publicly available copy of Longford’s 1911 text, Longford relied on the goodwill of the Japanese Ambassador, the Consul-General in London, as well as the Secretaries of the Embassy and Consulate-General “in elucidating obscure points in ancient history.”5 Longford’s preface sums up the confluence of two imperial interests: Japan converted “potentialities into realities of industrial and commercial wealth” as Britain invests in “the future status of our ally and in the political balance of the Far East.” The section on Korean history as a Japanese Protectorate reiterated the narrative of imperial salvation and modernity amidst Korean corruption and dysfunction.6

This analysis of a simple and almost uncritical presentation of the history of Korea in Terry’s guidebook shows how imperial texts have aligned to reinforce the Japanese imperial image of Korea, even as Japan was still subject to Terry’s Orientalist writing. Even in a colonial model of “Occidental” tourist-centric writing, this confluence of editorialising and knowledge transmission reinforces how Japan moderated and negotiated Orientalist treatment, leaving Korea twice removed from the mental hierarchy of Terry’s archetypal Western tourist.

- Shelley Baranowski et al., “Tourism and Empire,” Journal of Tourism History 7, no. 1–2 (May 4, 2015): 100–130. [↩]

- Hyung Pai, “Travel Guides to the Empire. The Production of Tourist Images in Colonial Korea” in Laurel Kendall (ed.) Consuming Korean Tradition in Early and Late Modernity: Commodification, Tourism, and Performance (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2010), 65-87. [↩]

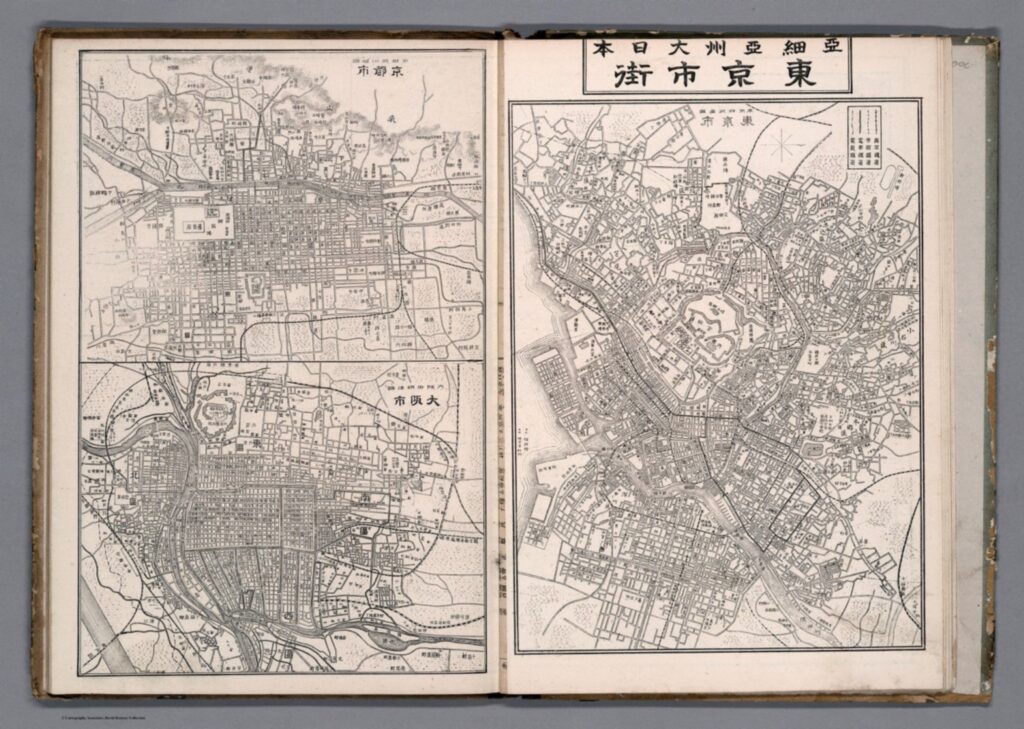

- Philip Terry, Terry’s Japanese Empire: A Guidebook for Travellers (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1914). [↩]

- Shelley Baranowski et al., “Tourism and Empire,” 126. [↩]

- Joseph H. Longford, The Story of Korea (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1911), v-vii). [↩]

- Longford, The Story of Korea, 351-365. [↩]

[7]

[7]

[3]

[3]