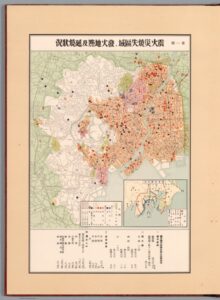

Eric Jennings chapter ‘Health Altitude, and Climate’ and his discussion surrounding malaria prevention methods within tropical climates brings forth another conversation regarding how contagious diseases may have been prevented within the same conditions. ‘Finding a viable escape from malaria and other tropical maladies was no trivial matter. Mortality for European soldiers and officials in Indochina remained on the order of 2 to 3 percent at the turn of the twentieth century.’1 Victims of malaria were able to be sent back to France or over to Japan, but in terms of contagious diseases other precautions would have needed to be examined. An example of this would be the bubonic plague which was a major concern for the speed in which it could spread. As Jennings argues, hot climates are a major concern for bacteria growth because they thrive within those conditions. However, the difference between these two diseases is malaria becomes a concern when those vulnerable remain within the same environment, but for the bubonic plague and other contagious diseases, the biggest concerns are formed when the infected move away from their previous environment.

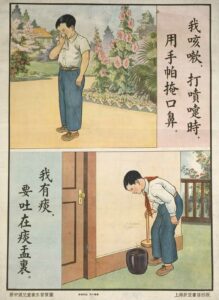

Trading ships were a predominant cause of contagious diseases being spread between countries. the close compact environment creates the perfect conditions for spreading diseases. In these cases, the most common precaution was to quarantine ports and to exterminate rats. ‘Southern Metropolis is cleaning up and ridding city of rats since plague scare.’2 Therefore, these instances throughout history give rise to concern regarding enclosed and densely populated spaces, especially when these spaces encounter a lack of sanitation protocols. Exposure to mosquitoes and rats that are contained within an environment in which malaria and the bubonic plague can thrive can become a matter of life and death, therefore, climate and environment as Jennings states was a vital aspect to research in order to understand the basic necessities for being able to remain within a tropical environment.

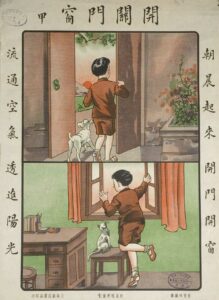

‘The new knowledge which enabled us to obtain ideal atmospheric conditions within buildings in tropical lands will have an even more remarkable effect of the transformation of these regions.’3

This coincides with Jennings other argument which centres around artificial climate. This type of climate allowed both the indigenous and Europeans to remain within a monitored space, which enabled them to remain healthy and away from any risks. Although Jennings only focuses on malaria, artificial climate has also proven useful of contained contagious diseases because the colder climate and high altitude created the perfect environment for not only deterring mosquitoes but for pausing bacteria growth.

‘He observed that children who had never left the plateau appeared healthy, while those who had travelled beyond it were sapped by malaria.’4

These findings enabled the tropics to become liveable, while also influencing other forms of artificial climate to take root within public and private environments because of bed nets and air conditioning. ‘Captain Tyler put forward the idea for improving the condition of hot, damp air, which he showed could be done by lowering the temperature of a room below dew point; in effect, providing a hospital ward or sick room with artificial climate.’5 Therefore, examples such as this highlight the evolving understanding of tropical climate and how studying altitude and climate can improve the understanding of health and hygiene. However, Jennings also provides a downside to these artificial climates due to the interior of these space being liveable, but once the occupants moved away from these spaces, they immediately became exposed to the raw climate conditions. It meant that space was still limited within the tropic, but it is undeniable that artificial climate still managed to create safe spaces to monitor and research malaria from a distance. Therefore, although diseases delayed progress within the tropics in terms of building settlements and expanding economies, what they did provide was a breakthrough within medicine and environmental control.

- Eric T. Jennings, Imperial heights: Dalat and the making and undoing of French Indochina (University of California Press, 2011) p.35. [↩]

- The Cable News – American, Iloilo Fighting for Her Health (1912) p.3. [↩]

- Hong Kong Telegraph, Artificial climate (1938) p.12. [↩]

- Eric T. Jennings, Imperial heights: Dalat and the making and undoing of French Indochina (University of California Press, 2011) p.42. [↩]

- Hong Kong Daily Press, Shanghai’s Damp Atmosphere (1912) p.8. [↩]