Spatial politics were central to the maintenance of Japan’s imperial empire.[1] A historical examination of tourism allows for analysis of how territory and geographical space were stabilised in the imagination of the Japanese public during the early 20th century. This blog post will explore the potential for understanding postcards as representative of historical mobility across this geographical space, both imagined and real. It will demonstrate this through comparing Japanese depictions of Korea through picture postcards produced in the colonial period. The arguments and ideas put forward in this post will form the basis of a longer analytical essay, and thus will aim to introduce the topic, highlighting potential areas for further development and synthesis.

“[Postcards] seem like shards of flash-frozen reality compacted into two dimensions, putative proof of having been there and seen that. They move over various forms of distance and time, while carrying with them ephemeral yet precious moments or sights to be appreciated, and then possibly forgotten.”[2]

There is a tendency in historical academia to treat postcards straightforwardly as either merely an embellished form of communication or simply a visual record, in much the same way as historical photographs. Whilst postcards do provide a valuable pictorial insight into the past, Hyung Gu Lynn argues that frequently scholars focus on the “aesthetic elements of the image” of postcards and neglect the socio-political context which an examination of their creation, distribution, and reception can allude to.[3] I argue that postcards inhibit both a sense of traversing space and traversing time. The sender of the postcard has travelled to an ‘unfamiliar’ space in order to purchase and post it back home. This is implicit in the meaning taken from the physical postcard itself, but also in the spatial imaginary it creates of the places photographed; thus the postcard has traversed space. Likewise, due to the nature of the postal service there is a passing of time between the act of the sender posting the card and it being received at its intended location; thus the postcard has traversed time. As Lynn states: “the postcard allowed for a journey into the afterglow of the recent past.”[4]

With this understanding, I will now compare three postcards of colonial Korea that, when analysed together, present a narrative of Japanese rule that emphasises colonial modernity. They are taken from the collection “The Views of Keijo.” Originally a 32 postcard set from the 1940s, only 29 of the postcards survive today.[5] The three postcards below all depict colonial Korea, but in dramatically different lights. Lynn argues that known changes to the urban landscape helps to place postcards (that often go undated) in time.[6] For example, the Government General Building in Seoul, Korea, was the subject of many postcards following its construction in 1926, as can be seen in the postcard below:

[7]

[7]

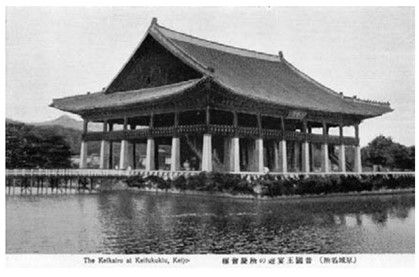

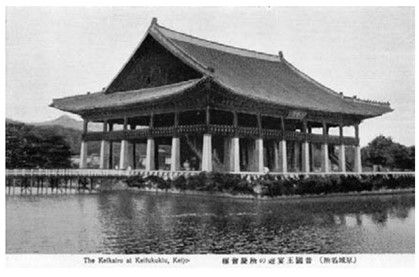

This postcard emphasises the modern architecture of the Government General Building, which sits on the previous site of the Korean Gyeongbok Palace. The demolition of valuable Korean historical and geomantic sites was a key facet of the Japanese occupation. In particular, new and modern Japanese buildings were located strategically and purposefully on old Korean sites. Part of the previous site was often left in ruins alongside the colonial site to demonstrate Japanese superiority.[8] These archaeological areas were then constructed into tourist spots, allowing the Japanese to select a specific representation of premodern Korean culture and civilisation to show the wider public.[9] The second postcard demonstrates this, depicting Gyeonghoeru Palace Hall:

[10]

[10]

In the picturing of these two locations in the format of postcards, Japanese forces could demonstrate to the wider Japanese, Korean, and international public their colonial strength and achievements, as well as transforming premodern Korea into a voyeuristic object rather than a lived reality. Combined, this created colonial Seoul as a desirable tourist destination.

In contrast, the third postcard shows the Korean neighbourhood located outside Seoul’s East Gate:

[11]

[11]

Postcards such as this, which displayed the thatched roofs of a Korean neighbourhood, helped to reassert a discourse of progress, or lack thereof, through comparison of these spaces with ‘modern’ Japanese buildings.[12] According to these postcards, which were placed alongside one another in a collection, modernity is presented as a result of colonial rule. This narrative implies the upward development of Japanese innovation in comparison to the illustrations of Korean society as in stasis.[13] Furthermore, the Korean people pictured in the postcards become themselves the object of touristic voyeurism and attraction.[14]

“This set of postcards nicely represents three themes typically encountered by Japanese visitors to Korea around 1940, namely examples of modernity introduced by the Japanese, evidence of Japanese efforts to preserve examples of Korea’s “once advanced civilization,” and evidence of the still primitive contemporary native culture.”[15]

Moreover, Lynn argues that colonial postcards “helped portray the colony as a place that was desirable because of its distance, its picture postcard exoticism.”[16] Through postcards, the imagined space of colonial Korea became closer to the Japanese metropole centre, and movement between the two was implied as easily achieved through modern technologies such as ship, rail, and post. At the same time, these postcards painted Korea as consisting of people culturally different (read: backwards) compared to the Japanese people receiving the cards at home.

There are several potential analytical areas around historical postcards which, if developed, would provide further insight into how they are representative of spatial mobility. For instance, the majority of postcards in surviving archival records are cards that remained unsent, likely being donated as a collection.[17] This speaks to the purpose of the cards as beyond simply stationary or for communicative means, suggesting they were tokens worth collecting and preserving. This, however, begs the question; is there more value to those historical postcards which were posted? In terms of examining their mobility, does the act of the postcard itself physically crossing geographical distance (and their rarity now) make it more valuable of study than those which were simply bought and collected? Such questions provide a useful starting point for further academic investigation of the topic.

[1] MacDonald, Kate (2017) Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan, Oakland: University of California Press, p. 2

[2] Hyung Gu Lynn (2007) ‘Moving Pictures: Postcards of Colonial Korea,’ IIAS Newsletter, 44: 8

[3] Ibid, p. 8

[4] Ibid, p. 8

[5] Ruoff, Kenneth J. (2010) ‘Touring Korea,’ in Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary, Cornell University Press, p. 109

[6] Lynn (2007) p. 8

[7] The Government General Building in Seoul, taken from the collection “The Views of Keijo,” as in Ruoff, Kenneth J. (2010) ‘Touring Korea,’ in Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary, Cornell University Press, p. 110

[8] Yoon Hong-Key (1988) ‘Iconographic Warfare and the Geomantic Landscape of Seoul,’ in The Culture of Fengshui in Korea: An Exploration of East Asian Geomancy, Lexington Books, p. 281

[9] Ruoff (2010) p. 109

[10] Gyeonghoeru Palace Hall, taken from the collection “The Views of Keijo,” as in Ruoff, Kenneth J. (2010) ‘Touring Korea,’ in Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary, Cornell University Press, p. 110

[11] Korean residential neighbourhood in colonial-era Seoul, taken from the collection “The Views of Keijo,” as in Ruoff, Kenneth J. (2010) ‘Touring Korea,’ in Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary, Cornell University Press, p. 111

[12] Lynn (2007) p. 9

[13] Ibid, p. 9

[14] Ruoff (2010) p. 111

[15] Ibid, p. 111

[16] Lynn (2007) p. 9

[17] Ibid, p. 8

[7]

[7]