Hong Kong today is seen as a modern metropolis with an efficient transport system, high-quality healthcare and high awareness of personal hygiene. Growing up in Hong Kong, I was taught as early as kindergarten to wash my hands with soap after taking a dump, recycle certain items in specific bins and most importantly not litter as it would attract bugs and rats. Additionally, in various public spaces like metro stations, wet markets and railings, there are ubiquitous colourful signs informing the population to not litter or spit on the streets, threatening them with a high fine.1 From a young age, I asked my parents why Hong Kong is so obsessed with hygiene and cleanliness, and my parents told me without hygiene education, Hong Kong would not be Hong Kong today. They told me that during their childhood they had to undergo hygiene education at school and constantly saw hygiene commercials and leaflets that warned them against unsanitary habits like spitting, blowing their nose in public, not washing vegetables, eating raw meat, and urinating in public. This signifies that hygiene in modern Hong Kong, unlike the notions of hygiene used to weaponise or justify imperialism like the case of the Japanese blaming Koreans in Keijo2, the British Hong Kong government starting in the late 60s devolved powers to locally-educated individuals to educate the lower classes through indirect means which is the main focus of this blog. To illustrate my point, I will be focusing on a newspaper report regarding hygiene from the Wah Kiu Yat Po published in 1972.

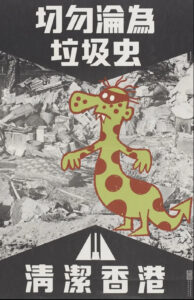

Figure 1: Lap Sap Chung poster in the Clean Up Hong Kong campaign, extracted from: https://zolimacitymag.com/lap-sap-chung-monster-kept-hong-kong-clean-ah-tak/

Above is the illustration of Lap Sap Chung which translates to rubbish bug which is a fictional character created by cartoonist Arthur Hacker.3 Lap Sap Chung was created as a method to appeal to Hong Kong residents because its unsanitary behaviour included littering and dirtying the streets, which was a massive problem in Hong Kong that led to diseases and deaths. By having a figure to ostracise those bad behaviour, it gives the incentive for Hong Kong people to work hard to clean up their city and foster a sense of identity to showcase what being ‘civilised’ and ‘modern’ is like. Unlike the colonial mentality of sanitation as per the readings, the campaign does not directly imply that the local Hong Kongers are dirty compared to their British overlords but rather it is everybody’s collective effort to maintain a clean Hong Kong. It is in reflection of the changing attitude towards governance as after the 1967 riots, the British colonial government realised that in order to prevent the spread of communism’s appeal and discontent among Hong Kong residents, improving livelihoods through education and concerted efforts are crucial to ensuring it.4

Drawing from the Wah Kiu Yat Po’s newspaper report on 9th September 1972, it showcases a headline in which residents caught violating the laws of public hygiene will be fined HKD$1000 and the second offence increasing to HKD$2000, somewhere around the sum of nearly a thousand pounds in today’s money.5 Although hefty fines were proven to be ineffective as in the case of Korea under Japanese rule and Singapore under the British colonial government, the main difference that differs Hong Kong’s case than the other two cases is the use of the Lap Sap Chung. As the article says, the board director of the ‘Clean Hong Kong Campaign’ was headed by a local, Wong Mong Fa, who quotes that the first step of advertising the campaign is declared a success and that the second step involves education. In order to succeed, the use of inspection teams to inspect every apartment block and verbally educate the residents about the laws regarding sanitation. In addition to the teams, leaflets, radio broadcasts, commercials, and newspapers will also be utilised to complement the efforts of the inspection teams. This showcases that the British colonial government was different from their attitudes towards Singapore in6 where the locals and British colonial officials were pitted against one another in the late 1930s, the 1970s in Hong Kong showcased how getting the locals to cooperate through increasing local involvement is actually a much better solution as educating the lower classes and ensuring citizens understood the laws thoroughly. This demonstrates how the involvement of different factors is needed in order to increase education and awareness about a hygienic society.

In conclusion, the example of Lap Sap Chung is widely regarded as a success as Hong Kong’s previously dirty streets have witnessed a massive improvement, and kids of individuals who grew up under the ‘Clean Hong Kong’ campaign like myself have seen the long-term effects of effective hygiene education not through just school but through digital and print media. Local involvement and the absence of racial ostracisation is what drive public health campaigns forward.

- Steve Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong, 2003 [↩]

- Todd. A Henry, Assimilating Seoul: Japanese Rule and the Politics of Public Space in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 Ch 4 Civic Assimilation: Sanitary Life in Neighbourhood Keijo [↩]

- https://zolimacitymag.com/lap-sap-chung-monster-kept-hong-kong-clean-ah-tak/ [↩]

- Steve Tsang, A Modern History of Hong Kong 2003 [↩]

- https://mmis.hkpl.gov.hk/search-result?p_p_id=search_WAR_mmisportalportlet&p_p_lifecycle=0&p_p_state=normal&_search_WAR_mmisportalportlet_keywords=%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F&_search_WAR_mmisportalportlet_hsf=%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F&_search_WAR_mmisportalportlet__cnsc1002_WAR_mmisportalportlet_formDate=1698495896489&p_r_p_-1078056564_actual_q=%28%20verbatim_dc.collection%3A%28%22Old%5C%20HK%5C%20Newspapers%22%29%20%29%20AND+%28%20%28%20allTermsMandatory%3A%28true%29%20OR+all_dc.title%3A%28%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F%29%20OR+all_dc.creator%3A%28%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F%29%20OR+all_dc.contributor%3A%28%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F%29%20OR+all_dc.subject%3A%28%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F%29%20OR+fulltext%3A%28%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F%29%20OR+all_dc.description%3A%28%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F%29%20%29%20%29&p_r_p_-1078056564_new_search=true&p_r_p_-1078056564_q=%E8%A1%9B%E7%94%9F&p_r_p_-1078056564_freetext_filter=%E6%88%BF%E5%B1%8B&p_r_p_-1078056564_freetext_filter=%E7%97%85%E6%AF%92&p_r_p_-1078056564_curr_page=1&_search_WAR_mmisportalportlet_jspPage=%2Fjsp%2Fsearch%2Fcnsc05.jsp [↩]

- Yeoh, Brenda, Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore Ch 3 Municipal Sanitary Surveillance, Asian Resistance [↩]