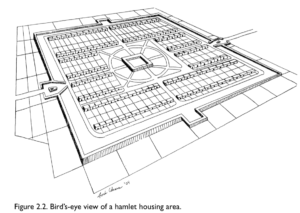

Utopian planning for large, populated spaces such as towns and cities are usually based around the idea of a booming economy and an equal social space. Utopia is usually expected to be an idea of peace and prosperity, but for Manchuria and Taiwan when they were under Japanese occupation, this idea of utopia was built on nationalism, which aimed to create a safe space for Japanese immigrants all while keeping everyone else out. David Tuckers, ‘city planning without cities’ responds to the idea of utopian space, by explaining how areas within Manchuria were planned with the concept of wide streets, sturdy housing, and well-placed sanitation efforts. However, what is interesting his analysis is that he continues on to explain that these spaces were to be created within defensible walls, all while enabling each household to have defences on hand If their ‘walled space’ were to be attacked. These walled spaces can be highlighted within the diagram bellow, which allow an understanding of just how organised these controlled spaces were.

‘Inside the wall is a ring of defensive open space, then a perimeter defensive road around the housing.’1

Therefore, what this concept of utopian spaces highlights is how much control and order has been built into urban planning. The extent of this control and order can be witnessed within the Japanese empire, especially within Manchuria and Taiwan where there was a high chance of being attacked by China or native populations. However, the installation of control is different when comparing Manchukuo and its supposed ‘blank slate’ or ‘white page’ to the Formosa Island within Taiwan, due to Japan having different protocols to initiate control.

‘The Japanese, after a series of struggles, lasting through several years, have eventually succeeded in putting down the disturbances; have introduced a form of government suitable to the welfare of the island people, and have effected general improvement in all directions, thus eliminating the bad social systems and encouraging good qualities of the people.’2

These utopian ideas within the Japanese empire, seem to stem from the idea of imposing Japanese qualities onto others, therefore, ensuring that the Japanese identity remains intact through not only initiating specific behaviours, but by also building spaces that would ensure that Japanese immigrants within the colonies would feel at home. These ideals were imposed all over the Japanese empire to ensure that the strength of the empire was displayed, while also ensuring that modernisation would be a quick and efficient process. The motivation behind this drive for modernising the Japanese empire is argued to be the result of competing with western powers.

‘Together architects used both architectural styles and new technologies to identify Japanese society as being culturally and technically sophisticated as any power.’3

Therefore utopian space became blurred and disjointed due to the desire to be the best and most efficient nation, while also ensuring that no one could take that power away. Through both David Tucker and Bill Sewell’s texts regarding the Japanese utopian spaces, the methods in which Japan used to colonise its empire become connected despite how different Taiwan, Manchuria and Korea were, because of the ultimate goal being to create a space that complimented the Japanese identity, while also ensuring that a level of safety and control was created. However, this ultimately broke down the utopian idea of the Japanese empire, because this control highlighted the social and cultural gap between Japan and its empire, which resulted in creating a hierarchy.