The focus of this blog post is how the traditional game sugoroku was utilised by popular Japanese women’s magazines to aid in their purpose of educating and promoting women to the ideal of the modern woman, family and hone. Both progressive and conservative in aspects, the game is ideal as an accessible educational tool as its tactile, playable nature gives the illusion of agency and control for its players, but ultimately the boards end in one fixed, limited goal which, in the gendered context of Pre-war Japan, was being rewarded for being a good modern housewife and mother, either with fashion or by a happy family. Largely the examples will be drawn from New Years editions of Fujin Sekai (Women’s World) from 1912-1919, however when relevant a few other sugoroku boards will referenced from a similar context.

In the early to mid 20th century in Japan, women’s magazine acted as a key tool in shaping and promoting the idea of the modern Japanese woman and the modern Japanese home. This was articulated in a number of ways, including instructive articles, recipes, advice columns and educational illustrations and pictures. Media played an important role in controlling how modern Western ideas could fit into Japanese traditions and how Japanese cultural strategies fitted with Western practices. Indeed, Jordan Sands comments that media potentially played an even more crucial role in the Japanese modernisation process before WW1 than the West as, unlike the latter, modernisation was first experienced as an outside foreign influence rather than an immediate consequence of industrialisation. Consequently, images of mass consumerism were experienced in Japan before mass consumerism itself (1). Therefore, before WW1 these magazines acted as aspirational guides to a lifestyle in transition which were not yet fully achievable.

The rise of these popular woman’s magazines coincided with educational policies that expanded women’s access to literacy and higher schooling. Some magazines in fact, saw their role as covering subjects which they viewed the women’s education system was lacking in. Educators and intellectuals wrote articles providing moral and intellectual guidance to higher school graduate, although they did also eventually target lower middle and working class women. One of the earliest mass circulation women’s magazines was Fujin sekai (Woman’s World, 1906) which was considered the leading magazine for the ordinary woman and, Barbara Sato argues, was the true pioneer of housewife centred magazines. focusing on women’s life after marriage, specialising in family orientated articles (2). Given Fujin Sekai ordinary women orientated demographic, and the reality that only a limited number of families could afford to have professional housewives, the portrayal of Shufu was largely aspirational ideal, than a grounded reality. Indeed, a key aim of Masuda Giichi, the editor in chief of the magazine, was to promote a popularised conception of self-cultivation in his readership, one that would allow personal fulfilment through practical strategies not available through the experience of women’s education system. Evidently, this was responded to well by female readers, as a Tokyo based survey in 1922 found that 70% of participants subscribed to women’s magazines because of their focus on self-cultivation (3). While, this practical agency to shape one’s own identity might seem a progressive break in literature for women, Giichi’s overall philosophy was that women’s fulfilment was only a step in woman’s ultimate mission was to be a good wife and a mother, and thus her self-cultivation was largely contained to the space of the home (4). This brand of controlled agency and self-expression is made manifest in their chosen medium of sugoroku.

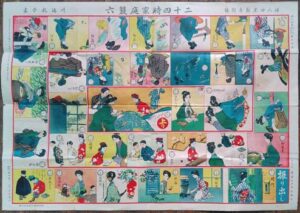

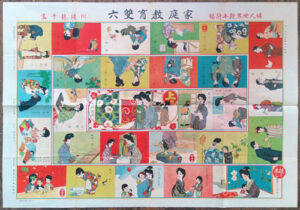

To understand why sugoroku was chosen as a strategy for these magazines, its important to provide some background context on the activity. Sugoroku is a traditional game in Japan which originated in two forms. The first ban-sugoroku was a game close to backgammon imported from China in 7th century which fell into obscurity, the other was the more popular e-sugoroku which emerged in the 13th century and was a largely image-based game. The gameplay, most closely resembling snakes and ladders, involves players beginning at singular/different start place, rolling a dice, landing on an image, and then following the instructions on said image. The aim is to end at the singular/different end points. The below examples, perhaps because they had a firm educational narrative to push, seem to have one single start and end point. Cheap and easy to make, they found popularity in the Meiji period in a variety of different magazines, covering a range of religious, historical, social and political topics. The main examples listed below are from Fujin Sekai, and the majority of them are from special New Years Day editions. This temporal conformity is telling given that sugoroku was considered a classic New Years day pastime for all the family (5). This highlights why sugoroku should be seen as a powerful educational tool in the magazines arsenal, because it was not only a highly accessible in terms of age and literacy, but also because it ingrained expectations of the modern housewife and the modern home not just to women readers, but to their entire family.

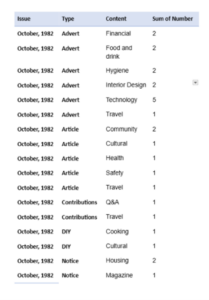

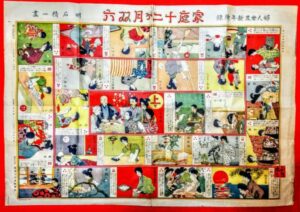

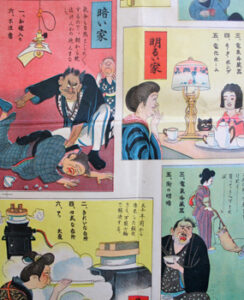

Kawabata Ryushi, Nijuyon Toki Katei, Fujin Sekai, 1912, accessed via Richard Neylon, Richard Neylon Rare Books, 12/11/2023

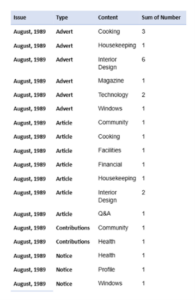

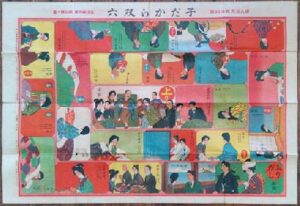

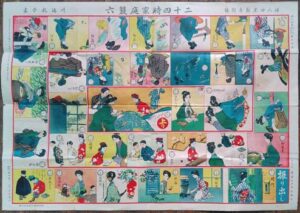

Kawabata Ryushi. Katei Kyoiku Sugoroku, Fujin Sekai, 1915, accessed via

Richard Neylon, Between Black Ships and B-29s (richardneylon.com) 12/11/2023

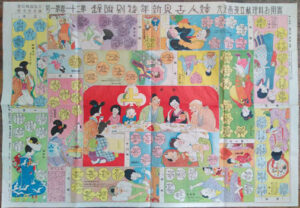

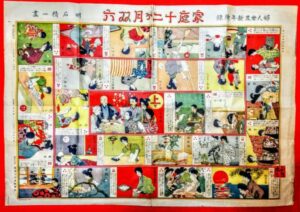

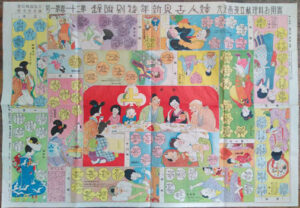

Akashi Seiichi, Katei Ju Ni Kagetsu Sugoroku, Fujin Sekai, 1917, accessed via

Richard Neylon, Between Black Ships and B-29s (richardneylon.com) 12/11/2023

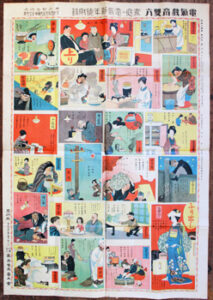

Akashi Seiichi, Fujin Nama Hi Tate Sugoroku, Fujin Sekai, 1918 , accessed via

Richard Neylon, Between Black Ships and B-29s (richardneylon.com) 12/11/2023

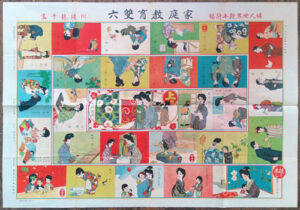

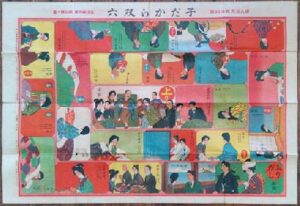

Akashi Seiichi. Kodakara Sugoroku, Fujin Sekai, 1919, accessed via

Richard Neylon, Between Black Ships and B-29s (richardneylon.com) 12/11/2023

Three of the five examples are structured around the idea of the day/year of the life of a busy housewife. The two exceptions are Fujin Nama Hi Tate and Katei Kyoiku, which tracks a women’s life from birth to adulthood. These Sugoroku boards are also the only games whose end goal isn’t a happy family, but becoming a fashionable, presumably wealthy, modern woman. Before noting the similarities in games, a notable absence from all the above Sugoroku boards is any orientation in terms of location with only minimal references to home interiors. Perhaps this is because the magazine influenced interior aesthetic through other means – photographs – or at this stage interior design wasn’t yet a focus in these magazines – although intriguingly Katei Ju Ni Kagetsu board has a panel of a woman painting a surface – but the central focus here seems to be teaching spatial practices in the home rather than instructing how to shape the home explicitly. Images that seem to appear in all of the boards are cooking (often multi-generational) cleaning (most commonly laundry or cleaning the floor), figures in windows (with activities being performed on either side of the window), and, perhaps most progressively, reading and writing and the teaching of these skills to children. Elements of modernity that can be seen through the above trends are: the cooking that seems to be being performed standing up rather than the traditional position of on the floor, and similarly in Katei Ju Ni Kagetsu and Kodakara boards, there is a practice of family tea/meal gatherings, rather than the traditional individual dinner trays for the patriarch (6). Notably however, in the case of Kodakara’s panel, while the wife appears to be above the rest of the family, ultimately only the patriarch is seated in the new furniture of the armchair. The Shufu may have been the household manager, but she was still under a patriarchal system. The imagery of the window and its emphasis of what’s inside and outside seems to play into the discourse of private and public sphere that the concept of the home initiated. Finally, the promotion of literacy and continued education throughout a women’s life, possibly speaks most clearly to the theme of self-cultivation.

It’s worth noting three of these works are by the same artist, and so its valuable to look at examples from other artists and other publications.

Fujimoto Katao. [Jitsuyo Oryori Kondate Manga Sugoroku]. Tokyo, Fujin Sekai 1926, accessed via Richard Neylon, Richard Neylon Rare Books, 12/11/2023

Despite its focus on cooking, this board has many of the same elements as listed above. There are two notable elements of this design however, firstly is the presence of the dining table, a new furniture edition, and more importantly, a panel that indicates a man’s involvement in household world (7). Whether this is a remanent from more traditional times when household labour wasn’t so clearly divided by gender, or a reflection that such a division was unrealistic even in ‘modern’ times, it’s an noteworthy image given the strict roles established in previous boards. Indeed, it is not out of the realm of possibility Sugoroku boards were used for subversive purposes.

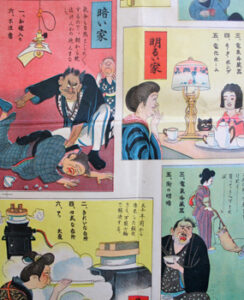

Maeda Masujiro. Onna Tenko Sugoroku, Osaka 1915, accessed via Richard Neylon, Richard Neylon Rare Books, 12/11/2023

While graphic gender role reversals were often used for antifeminist purposes, the abject horror and disgust on the man’s face at undertaking these household tasks seems a compelling argument for the inequality of the household labour and women’s submissive role.

While examples like the above can be speculated on, many of the boards did seem to be conservative in tone. This was not just seen within the framework of educational women’s magazines, but also in a commercial framework.

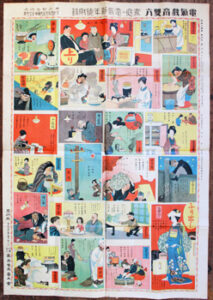

Shimizu Taigakubo, Denki Kyoiku Sugoroku, Katei no Denki, 1927, accessed via Richard Neylon, Richard Neylon Rare Books, 12/11/2023

This sugoroku board by the Household Electricity magazine evidently promotes modernity through the numerous new technologies it highlights, and additionally through its emphasis of hygiene iterated through the new presence of the cleaning and cooking frock apron. More striking however, is that it doesn’t just promote this new technology through images of aspirational lifestyles, but also by the danger of not innovating. In this board more so than the others examined in this post, there is the presence of characters making right and wrong choices, Making sensible proactive steps will result in the goal of a happy family, but passivity and not staying up to date could result in a wife being beaten. This sugoroku then highlights the more brutal tactics magazines will take to achieve their agenda of modernisation and consumerism,

Ultimately, then sugoroku could act as varied and evocative strategy in the magazines, and the wider society’s, construction of the aspirational ideal of the modern housewife and modern home. In the period before mass consumerism had fully taken shape in Japan, these games largely emphasised spatial practices for women to undertake. While the promotion of literacy and education spoke to some genuine desire to offer women opportunities of personal fulfilment, these practices largely worked to make the woman the ideal wife and mother which, amongst other strategies, included incorporating foreign ‘modern’ practices into the home – cooking standing up, cooking with an apron and collective family meals. Overall sugoroku, specifically those produced for a publication, provides a rich source of analysis about gender, family and home in 20th century Japan, particularly because it was highly accessible, and it was played as a family unit.

(1) Jordan Sand, House and Home in Modern Japan: Reforming Everyday Life 1880-1930, (Harvard University Press, 2005), p.14

(2) Barbara Sato, “Gender, consumerism and women’s magazines in interwar Japan.” In Routledge handbook of Japanese media (Routledge, 2018, pp. 39-50, pp.41-42

(3) Sato, ‘Gender, Consumerism’, p. 46

(4) Ibid.

(5) Flickinger, Susan, Barbara Podkowka, and Lori Snyder. “A Window into Modern Japan: Using Sugoroku Games to Promote the Ideal Japanese Subject in the Early 20th Century.” (2015), pp.1-9, p.1

(6) Sand, House and Home, p.84, p.73-74

(7) Ibid, p.35