In 1898, after U.S. forces had invaded during the Spanish-American War, the Philippines was ceded as a concessionary territory to the U.S. The American colonial period lasted until 1946. During this era, there was an increase in immigration to the Philippines, as U.S. forces attempted to “create a country and a people in the American image”.[1] Kiyoko Yamaguchi examines the Philippine architecture built under this influence, and argues that buildings constructed during this time labelled as ‘American’ were not built by U.S. colonisers, but by the elite urban Filipinos in what they interpreted to be the ‘American’ style.[2] In actuality, immigrants from America isolated themselves and their community through social clubs and viewed their residence there as temporary.[3] This post will examine how these colonial residents became uniformly ‘American’ by examining the spaces, both perceived and physical, in and around exclusive social club houses in the Philippines.

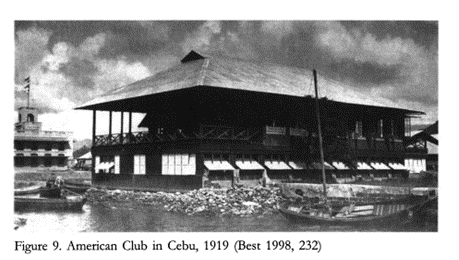

[4]

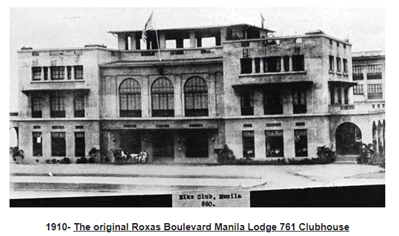

[4]

[5]

[5]

Much of the history written about the Philippines relies on oral and biographical histories, mainly originating from the memories of American immigrants who grew up there during the colonial period. Consequently, narratives of the American lifestyle during the 1920s and 1930s in particular are often filled with idealistic notions of “serenity”, and take the social segregation of Filipinos and Americans as the norm.[6] Examine this 1939 excerpt by Walter Robb:

“Filipinos were accustomed enough to dealing with strangers… On their part the Americans displayed a remarkable adaptability; without destroying what existed, they set to building upon it and to patterning for the Philippines a government of the American type that was effective against a Latin background…”[7]

Or view these quotes from Merv Simpson, manager at the Corinthian Plaza in Manila, talking about his life in the Philippines in the 1930s:

“It was a peaceful life. We had parties, or at least my parents had parties, but nobody got bombed, at least as I can remember… Before the war we didn’t play with Filipino kids or associate with them very much. It wasn’t any snobbish thing; we just didn’t do it.”

“It was pretty sheltered. We went to the American School. No Filipino kids [but some] mestizos… I’d ask my mother – I’d want to go to the Polo Club, it would be Saturday morning – so she’d give me a peso. That was big dough back then. I’d take a taxi out there… At the Polo Club we used to swim, badminton, bowling, tennis – it was a nice life. We would just sign [for the bill]…”[8]

Recorded in this nature, the colonial spaces of the Philippines become subject to consumption through sentimental regard, which Vicente L. Rafael argues allows for a domestication of “what is seen as native and natural into aspects of the colonial, which is at once also national.”[9] He maintains that through these types of historical accounts, colonialism is invested with a sense of domesticity, allowing for the pervasiveness of Western gendered and racialized notions into the colonial experience.[10] Thus, the colonial experience recounted here simultaneously normalises and sentimentalises the racial divisions of the American period. One of the key ways in which this occurs is through mentions of the social clubs that American residents in the Philippines engaged in, but which Filipinos were barred from.

Yamaguchi recognises this, and through her discussions develops the idea of an ‘imagined America’ in the Philippines. She explores how the self-perception of U.S. citizens living in the Philippines evolved by analysing the exclusive social club houses set up by the colonial American community. Many of the Americans who arrived in the Philippines were second- or third-generation European immigrants to the U.S. themselves, and so their American identities became strengthened by the role they played in these colonial communities.[11]

“The Americans were not Filipinized by living in the Philippines; they became more self-consciously and assertively American, a fact most apparent in the club premises, where they confined themselves in particular buildings.” [12]

Yamaguchi argues that these exclusive clubhouses prescribed an American “uniformity” to the blurred identities of these colonial residents.[13] The diversity of the cultural backgrounds of these Americans meant it was likely they would have never befriended one another if they had met in the U.S.. Because of their location in the Philippines, and through the sociality of the spaces offered through membership to these clubhouses (spaces which became the metaphorical petri dish for colonial politics), these differences faded in the face of attachment to a specific U.S. identity.[14] The spaces within the clubhouse also solidified other identities, namely, that of the Filipinos who they excluded. The Filipino residents in these areas were barred from membership despite the fact that many Filipino urban elites were often just as wealthy as their American counterparts.[15] This exclusion also sought to define the Filipino identity categorisation, vis-à-vis what was not considered American.

Thus, the architecture of this period reflects the nature of the changing social groups in the Philippines, and articulates Filipino elite ambitions and interpretations of ‘American-ness’. These social clubs allowed for the standardisation of the American imperial lifestyle and identity, whilst simultaneously sentimentalising a social hierarchy based on race.

[1] McCallus, Joseph P. (2010) The MacArthur Highway and Other Relics of American Empire in the Philippines, Potomac Books. (page number unavailable).

[2] Yamaguchi, Kiyoko. “The New ‘American’ Houses in the Colonial Philippines and the Rise of the Urban Filipino Elite.” Philippine Studies 54, no. 3 (January 1, 2006): p. 413-14

[3] Ibid, p. 447

[4] Best, Jonathan (1994) Philippine album: American era photographs 1900-1930, Makati: Bookmark, p. 232

[5] ‘Lodge History: The Manila Elks Lodge 761 in its 114th Year’, https://www.manilaelks.org/about-us/manila-elks-lodge-761/lodge-history/ [Accessed 28/10/21]

[6] McCallus (2010) (page number unavailable)

[7] Ibid (page number unavailable)

[8] Ibid (page number unavailable)

[9] Rafael, Vicente L. (2000) ‘Colonial Domesticity: Engendering Race at the Edge of Empire, 1899-1912,’ White love and other events in Filipino history, Durham, NC: Duke University Press (page number unavailable)

[10] Ibid (page number unavailable)

[11] Yamaguchi, (2006) p. 424-26

[12] Ibid, p. 426

[13] Ibid, p. 425

[14] Yamaguchi, (2006) p. 426; Rafael, (2000) p. 56

[15] Yamaguchi, (2006) p. 431

Bibliography

- Best, Jonathan (1994) Philippine album: American era photographs 1900-1930, Makati: Bookmark

- McCallus, Joseph P. (2010) The MacArthur Highway and Other Relics of American Empire in the Philippines, Potomac Books. (page numbers unavailable)*

- Rafael, Vicente L. (2000) ‘Colonial Domesticity: Engendering Race at the Edge of Empire, 1899-1912,’ White love and other events in Filipino history, Durham, NC: Duke University Press (page numbers unavailable)**

- Yamaguchi, Kiyoko. “The New ‘American’ Houses in the Colonial Philippines and the Rise of the Urban Filipino Elite.” Philippine Studies 54, no. 3 (January 1, 2006): 412–51

- ‘Lodge History: The Manila Elks Lodge 761 in its 114th Year’, https://www.manilaelks.org/about-us/manila-elks-lodge-761/lodge-history/ [Accessed 28/10/21]

*Limited access available to book online due to lack of institutional access, quotes taken from ‘Look inside’ excerpt available on Amazon listing: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B005CWJMFU/ref=dp-kindle-redirect?_encoding=UTF8&btkr=1 [Accessed 28/10/21]

**Limited access available to book online due to lack of institutional access, quotes taken from excerpt found through Project Muse: https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/2618760 [Accessed 28/10/21]