Having realized that I erroneously wrote two blog postings on secondary sources (because of how interesting the ideas that they offered were), I will do my penance and analyse a primary source that I gathered myself over the summer. The image in question is sourced from Haw Par Villa, one of the zaniest places in Singapore with the most cursed energy I have ever seen from a recreational space. The park itself was the pet project of the two brothers, Aw Boon Haw (胡文虎) and Aw Boon Par (胡文) that founded and ran a lucrative empire selling Tiger Balm, a medicinal salve that is still popular throughout Southeast Asia today.

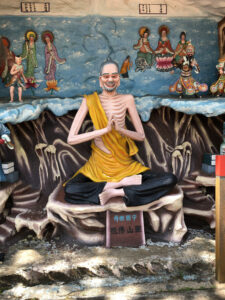

Due to the sheer chaos that is the nature of this source, I am unsure as to whether it’s even possible to make a clear analytical point. One could discuss the synthesis of Daoist and Buddhist iconography in having Bodhisattvas, Buddhas, what I would assume to be Nezha and Dharmapalas (protectors of the Dharma) in the same image or even just the artistic choice of how these figures were depicted. As such, I have decided to focus purely on the significance of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas depicted in the image.

The diorama appears to be attributed to the Lingshan Buddhist Group (霊山佛祖) based in Chaozhou (中国潮州). Further investigation showed that the place is indeed close to the city of Chaozhou, but is still a fair distance from it. Historical records of this particular Buddhist group are likely to be fairly scarce, and may have indicated that they paid for the particular diorama. Even the character for “Ling” is difficult to find and seems to either have been miswritten, or no longer exists in the current Chinese lexicon so much so that I was unable to input the exact character into my phone or computer.

The main figure depicted is an emaciated Buddha, a reference to the Gautama Buddha’s experience starving himself when he first left royal life. This form of voluntary starvation was seen as a form of ascetism and a symbol of how a person could gain ultimate control over their body (to the point of rejecting sustenance). The quite hilariously done, poorly-installed cord linking the larger statue to a smaller bowing figure in the background is a depiction of him achieving enlightenment (shown as ascendance) and meeting what I would assume to be the Buddhas of the Three Ages.

Typical descriptions of the Buddhas of the Three Ages would include Maitreya (representing the Future) and Gautama Buddha (who is notably absent in this depiction). The Prajnaparamita Sutra refers to the Buddhas of the Three ages in a single phrase (tryadhva-sarva-buddhāḥ) perhaps suggesting that the three are one reincarnated. It is without a doubt that the choice of these three specific Buddhas are deliberate and have enormous significance to story, but at a level that I cannot discern nor understand.

Maitreya is clearly depicted with his massive earlobes and belly, and Bodhisattva Guanyin with her classic hairstyle and vase. However, there is a Buddha that is difficult to discern based purely on appearance. The mysterious third Bodhisattva with a Ruyi (Chinese Sceptre). The plaques right above them is meant to clarify which Buddhas are being depicted, with Maitreya and Guanyin being fairly recognizable as “弥勒佛”and “观世音菩萨” respectively. The middle name, seemingly depicting the figure on the far right “世济佛菩萨” is mentioned in many Mahayana scriptures but is unknown to me.

The reasoning choice of Buddhas in this specific diorama may reflect which Buddhas the artists considered culturally important in this era. Or it may be an entirely arbitrary choice. Whichever it is, it certainly a fascinating and curious piece of historical Buddhist art.