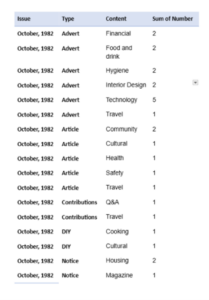

This blog explores findings from a quantitative analysis of the contents of HDB Our Home Magazine. Specifically, the first issue (October 1972), an issue in its 5th year (October, 1977), an issue in its 10th year (October, 1982), and its final issue (Aug-Sep, 1989). ‘Our Home’ was a magazine run by the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in Singapore from 1972-1989, free to its residents (and 50 cents to non-residents) it provided articles and advice on cooking, housing and cultural topics. This study looked at the quantity and genre of different types of content in the magazine issue. Due to language limitations, only the English content is included here. Overall, the results suggest that while there was a surprising lack of dialogue between advertisements and articles; while the advertisements pushed the narrative of modernity and domesticity through products and services related to modern interior design and new technology, the editors of the magazines were far more concerned with highlighting the harmonious, diverse community of HDB.

Definitions:

Contributions – Content that included contributions from the community (e.g. Q&A, recipes, opinions)

Notice & Housekeeping – Content that is presented as important information to residents (e.g rent info, maintenance, housing reminders)

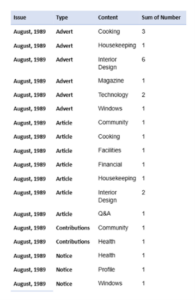

Fig. 1-4 Breakdown of the spread of different types and content topics in each of the 4 magazine issues respectively

While this is a limited data sample, spaced at appropriate intervals over the magazine’s run, some insights can be gleamed. Advertisements are the category to display the most changes over the 4 issues, beginning with 10 different advert genres initially, then having an unusual year in 1977 with only 2 genres and 6 adverts in total, before stabilising at 6 different types for the next two issues. While this likely fluctuates in issues beyond the data set, I think the high number in the first issue is likely a reflection of the investors and the advertorial team not knowing what the magazine’s readership or purpose was yet. This uncertainty is present with both the adverts and articles in the featuring beauty and fashion in the first issue and abandoning them in the subsequent issues. Potentially, they realised they had broader appeal than just women, or perhaps the editorial team decided they wanted to mould the home, not the housewife. Either way, it’s clear they moved away from being a women’s magazine to being a home magazine. In terms of content the articles started to lean more consistently towards community and instructional guidance, while adverts focused on interior design and technology as their primary promotional content.

Fig. 5-6 Culminative number of different content type in advertisements and articles across the 3 magazine issues.

The breakdown of the technology adverts largely consisted of sound technology, cooking machinery and Sony products. The interior design adverts ranged from furniture salesrooms, tilers, and kitchen upgraders. While it would be tempting to use this to draw a parallel between HDB’s approach to technology and the modern home to what Tatiana Knoroz describes as an obsessive drive to keep technologically up-to-date in Japan’s mass housing of Danchi to justify its value as middle class housing, this magazine doesn’t support this link (1). While this may be the narrative of the adverts, none of these issues have an article about technology. Even in the 3 interior design article there is no push towards modern interior design, indeed in one of them compares a modern and traditional home interior and concludes they are both equally ‘cosy’ (2). Their focus is more on building community relations through profiles on people and communities, advice on living in HDB residences, and instructional articles. This is reflected in the 3 languages that the magazine is presented in. Another technique they are keen to push is community contribution to the magazine, in the contents page of the four issues, but contribution consistently remains low in this data set, perhaps indicating a lack of engagement or desire for this type of interaction.

Ultimately then, while this small quantitative study seems to mirror some narratives of modernity’s effect on post-war mass housing, the articles’ themselves don’t seem to mirror the same drive to modernise and westernise interiors and equipment. While adverts are a part of the magazine’s value system and narrative, the lack of dialogue between them in this data bears some highlighting.

Footnotes

- Tatiana Knoroz, Dissecting the Danchi: Inside Japan’s Largest Postwar Housing Experiment. (Springer Nature, 2022), pp. 41-112

- ‘Vast Variations’, Our Home (Singapore, House and Development Board) August-Sep, 1989, p.28

Reference list:

Our Home (Singapore, House and Development Board), October, 1972

Our Home (Singapore, House and Development Board), October, 1977

Our Home (Singapore, House and Development Board), October, 1982

Our Home (Singapore, House and Development Board), Aug-Sep, 1989