The Great Kanto Earthquake which leveled much of Tokyo and Yokohama in 1923 created an opportunity for reconstruction on an enormous scale and caused a shift in the population distribution as well as the aesthetic standards of the city. The utopian approach to rebuilding Tokyo after the earthquake mirrors Japanese attitudes towards Manchuria while also serving as a stark contrast of utopian ideals.

The event was described in the September 1923 issue of the American publication Japan Society as “The Greatest Disaster in History.”1 The earthquake and subsequent fire left “298,000 houses burned and 336,000 more shaken down,” in the journal’s initial report.2 A final estimate of its destruction was that around 45 percent of the structures in Tokyo were leveled, transforming it “from a bustling metropolis and imperial capital to a seemingly extinct city.”3

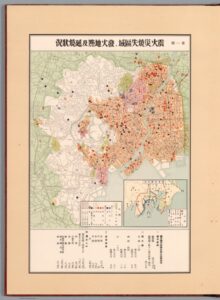

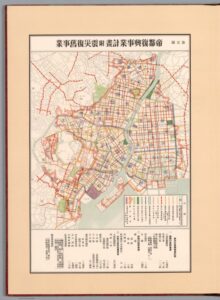

The scale of the destruction was interpreted at the time as “a moral wake-up call if not an outright act of divine punishment” but also, contrastingly, as a “golden opportunity.”5 At a time when utopianism and grand visions of urban planning were circulating in books like Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of Tomorrow, the earthquake essentially rendered Tokyo a blank slate upon which to rebuild. It literally flattened the city, creating “not only a unique, perhaps unparalleled opportunity to reconstruct Tokyo but the chance to arrest the perceived moral and ideological regress of Japan.”6 Efforts to not only reconstruct, but to renovate, beautify, and modernize Tokyo began. By 1930 the products of these initiatives could be visibly traced on a series of maps produced by the Tokyo City Government which illustrated the results of projects dedicated to restoration and new construction of parks, schools, hospitals, roads, bridges, and electrical facilities.7

In addition to government efforts to rebuilt the city itself, the earthquake triggered a flight from the city center to the areas surrounding Tokyo, increasing the suburban population and decreasing the density of the city. The suburb of Denenchōfu, planned and constructed in the years just before the earthquake, was modeled after the utopian vision of Howard’s garden city. The timing of its construction (completed in 1923) and its location outside Tokyo caused its population to increase dramatically after the earthquake.9 This suburban population boom was widespread according to Japan Society’s December 1925 issue, which predicted that “Under the Greater Tokyo system, in which all of these suburban towns will be included in the City of Tokyo—and it is expected that this can be realized within the next decade or so—the City of Tokyo will have a population equalling that of London.”10

Denenchōfu serves as an example of the change in Tokyo’s population distribution as well as a new emphasis on the aesthetic qualities of the city’s spaces. The architects of Denenchōfu placed a high value on the natural beauty of the development in accordance with Howard’s garden city ideal.11 The Tokyo government likewise invested in natural surroundings in its efforts to rebuild as evidenced by the excerpt in Japan Society’s May 1925 issue stating that “The Park Section of the Tokyo Municipality will plant 3,000 trees along streets in various sections of the city in May as part of the program to beautify the city.”12

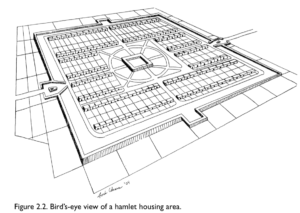

This utopian conception of Tokyo post-earthquake as a blank slate on which to modernize infrastructure, disperse the population, and beautify the city parallels how some Japanese planners and intellectuals envisioned Manchuria. The Japanese conquest of Manchuria after 1931, “provided a blank slate, or as city planners in Manchukuo put it, a white page, hakushi, on which ideal designs might be realized.”13 Ideal designs such as the Agricultural Immigrant Plan which envisioned utopian agricultural villages populated by Japanese farmers in northern Manchuria.14 In fact, “More than a few planners disillusioned by the resistance their plans faced in postearthquake Tokyo found planning on what they considered to be ‘blank pages’ in colonial Manchukuo more rewarding.”15 While the Agricultural Immigrant Plan was never realized, many architectural projects and modernization efforts were carried out in Manchuria.16 Like Tokyo after 1923, it served as a place in which to test utopian ideals.

Despite certain similarities in the conception of utopian plans, one of the stark contrasts between the “blank slate/page” of utopian planning in 1923 Tokyo and 1931 Manchuria was the ideology which accompanied it. Unlike the aftermath of the Kanto earthquake in which the perceived “moral regress” included socialism, for those censored for their contrary politics in Japan, Manchuria offered a blank slate of a different kind.

- Japan Society, About Japan 1920-1928 (Internet Archive, 2021), https://archive.org/details/about-japan-1920-1928/page/n5/mode/2up. [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Charles Schencking, “The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Culture of Catastrophe and Reconstruction in 1920s Japan”, in The Journal of Japanese Studies 34, no. 2: (Summer 2008), 296. [↩]

- Zenjirō Horikiri, 1. Areas afflicted by the earthquake and fire disaster, places where fire broke out and circumstances driving the spread of the fire [map], Tokyo City Government, 1930, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~334402~90102430?qvq=q%3Apub_list_no%3D%2210808.000%22%3Blc%3ARUMSEY~8~1&mi=11&trs=38. [↩]

- Schencking, “The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Culture of Catastrophe and Reconstruction in 1920s Japan”, 297. [↩]

- Ibid., 297. [↩]

- Zenjirō Horikiri, Teito Fukkō Jigyō Zuhyō, David Rumsey Historical Map Collection, Tokyo City Government, 1930. [↩]

- Zenjirō Horikiri, 5. Program for the reconstruction of the imperial capital [map], Tokyo City Government, 1930, https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~334398~90102426?qvq=q%3Apub_list_no%3D%2210808.000%22%3Blc%3ARUMSEY~8~1&mi=7&trs=38. [↩]

- Ken Tadashi Oshima, “Denenchōfu: Building the Garden City in Japan”, in Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 55, no. 2: (June, 1996), 146. [↩]

- Japan Society, About Japan 1920-1928. [↩]

- Oshima, “Denenchōfu: Building the Garden City in Japan”, 144. [↩]

- Japan Society, About Japan 1920-1928. [↩]

- David Tucker, “City Planning without Cities: Order and Chaos in Utopian Manchukuo”, in Crossed Histories (Honolulu, 2005), 55. [↩]

- Ibid., 53. [↩]

- Schencking, “The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Culture of Catastrophe and Reconstruction in 1920s Japan”, 323. [↩]

- Louise Young, “Brave New Empire: Utopian Vision and the Intelligentsia”, in Japan’s Total Empire (Berkeley, 1998), 242. [↩]